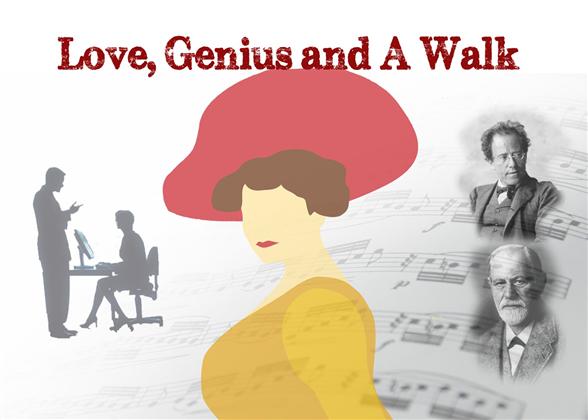

An artist’s love is probably one of the most favorite themes of all time and playwright Gay Walley undoubtedly succeeds in exploring it in her play, “Love, Genius and a Walk†with a combination of memorable quotes, relatable characters and expressive and emotional acting.

An artist’s love is probably one of the most favorite themes of all time and playwright Gay Walley undoubtedly succeeds in exploring it in her play, “Love, Genius and a Walk†with a combination of memorable quotes, relatable characters and expressive and emotional acting.

Playing along with the modern tendency for true stories, the play takes interest in the tragic life of an acclaimed Austrian composer, Gustav Mahler and features excerpts from his last piece, “Tenth Symphony.â€

Addressing such eternal themes as love, art, success and happiness, “Love, Genius and a Walk†tells two distinct stories simultaneously and is full of paradoxes. Luckily for the audience, Director Gregory Abels, finds a few visual ways to distinguish the stories and time periods from one another, so that it does not get confusing for the viewers. Firstly, there appears an obvious difference in clothing. The female characters from the past wear long old-fashioned dresses, while the modern ones dress according to the contemporary fashion. Secondly, during the cross-generational dinner party, one can distinguish one group from another by looking at their glasses.

Bringing the two parties together is definitely an unusual and bold move on the director’s part and it plays out well with the audience, although it seems to be a time-saver rather than an essential element of the plot. The two main stories are tightly interwoven. One tells us about Mahler (Paul Binotto) and his unhealthy marriage with the love of his life, Alma (Lara Hillier), whom he, busy with composing music, continuously pushes away. The other one deals with Gina (Kathleen Wallace), a writer working on the book about Mahler and her connubial relationship with Steve (Alexander Pepperman). When one is writing a book, he or she can imagine its characters as vividly as though they were a part of his or her own life, so Mahler’s reality, weaved into Gina’s, seems natural. Additionally, the side story tells us about the brief encounter between Gustav Mahler and the famous psychoanalyst, Sigmund Freud (Shelley Valfer).

Thus, three different geniuses, Mahler, Gina and Freud, take the stage. All three have lots of passion and faith in their work. Mahler’s talent lies in composing music. He devotes all of his time to his symphonies and leaves his wife, Alma, on the periphery. As he pays little attention to her, the woman finds consolation in other men. Years after his death, the composer’s life and music fascinate Gina, even though Steve tells her that no one cares about Mahler anymore and she should write a book that would sell more copies.

Money, however, is not Gina’s main concern (especially that Steve is apparently pretty wealthy). “I get value by making something,” she says. She admits that her way is full of thorns: her work earned few admirers, some criticism and a lot of indifference; still, she believes in her genius and perseveres. As far as Freud is concerned, we learn little about his life, but we see what influence his work has on other people, freeing them from their fears and insecurities, and we hope that Freud’s advice will help Mahler improve his relationship with Alma.

Sympathizing with the main character, we can’t help but notice that as an artist, he composes music about love and senses what his listeners will feel. However, when it comes to his wife, he fails to understand her emotional needs. Alma’s unfaithfulness is a call for attention. She loves her husband and cares for him, but he is so into his music that he barely has any time for her.

While Alma, at least, respects and supports Gustav’s creative work, Steve, being a practical man, considers Gina’s writing pointless because it has little monetary value. “An artist is a fool to be poor. Only the rich ones are successful,” he says, and although Gina disagrees with him, she can’t help feeling that she is an artistic failure, which brings even more tension into their relationship.

With emotions on the verge of boiling, a little bit of humor entertains the audience and puts them at ease. It works especially well during the Mahler-Freud encounter. The two men are conversing in the park, and passing by strangers recognize one or the other and approach the geniuses. The most hilarious character is a lady’s dog that is breathing heavily with its tongue out. The strangers are often portrayed with irony. For instance, a passerby recognizes Mahler and tries to flatter the composer, saying, “Such beautiful church music! It could have been written by Verdi!” The “compliment” aggravates Mahler because, first of all, he does not consider his work “church music” at all. What’s worse, he does not think much of Verdi, and takes the comparison for an insult. Binotto’s facial expression and gestures give away his character’s anger, showing us the other side of Mahler, which of a creative genius ready to stand up for his music.

As far as the acting goes, Hillier definitely wins the most applause. Her face portrays her character’s every emotion. It seems only natural that with all her fluffiness and liveliness, she cannot cope with her husband’s lack of attention towards her. Binotto’s Mahler comes across as an introverted artistic type who livens up only when talking about music, although Freud surely manages to win his interest and respect during their brief encounter.

Since the cast consists of only 11 people, many actors play several minor characters. Various hats and scarves momentarily refresh the characters’ outfits and show the change of scene. Jimmy Dailey plays both the part of Alma’s lover with a telling name Gropius and the one of Gina’s friend, Paul, who attempts to seduce her, using her frustration about Steve’s attitude. He plays the two lovers’ roles similarly, despite the generation gaps between them. Are all passionate lovers the same? That is the question.

Although the play deals with a particular historical figure, it raises eternal questions every generation strives to answer. What is love? Success? Fame? Undoubtedly, Mahler’s story is a tragic one; however, according to Valfer’s Freud, “Far worse is not to know who you are,” a piece of wisdom every one of us, including Gina, can use to our benefit. Maybe the real geniuses are those who know who they are and those who never give up on their dreams? Maybe to love is to be selfless and to demand nothing? Do we need the questions more than answers?

Leave a Reply