From the first time a puck was dropped on a sheet of ice in North America, hockey players have earnestly felt the need to defend themselves and their teammates through physicality. During most of this time, it appeared that hockey and fisticuffs were wed. However, over the past five years, NHL commissioner Gary Bettman and other high-profile league officials have sought to put a halt to the violence, much of which has been enjoyed for almost 100 years.

From the first time a puck was dropped on a sheet of ice in North America, hockey players have earnestly felt the need to defend themselves and their teammates through physicality. During most of this time, it appeared that hockey and fisticuffs were wed. However, over the past five years, NHL commissioner Gary Bettman and other high-profile league officials have sought to put a halt to the violence, much of which has been enjoyed for almost 100 years.

Though the league has attempted, ardently, to eliminate fighting from the sport, pockets of fans and media have felt that in doing so, the NHL was stripping the sport of its essence.

For many, fighting is a necessary evil and one that helps maintain the game’s classic norms of passion, courage and grit. Without it, many contend, the game becomes more about scoring and less about teamwork and toughness.

“Hockey is the only one of the four major sports with confines [where] a player can’t run out of bounds to avoid a hit,†said Hall of Fame broadcaster Jiggs McDonald, who has called over 3,200 NHL games over 45 years. “Some of those hits, the ones of questionable intent, lead to fights… But the more obvious is that hockey is the only sport to equip every player with a weapon – if they were to chose to use it that way.â€

In the late 1970s, the NHL had an influx of European players and the league underwent changes.

The European players, for the most part, were better skaters than the North Americans who had long dominated the league and, as a result, offensive production skyrocketed. However, with fighting being illegal in European leagues, incidents of dirty plays such as high-sticking, cross checking and tripping became more frequent. While most of the new players were reluctant to fight after committing the penalties, their North American teammates, who had grown accustomed to the league’s rough and tumble style, were more than willing to drop the gloves.

As the years went on, the frequency of questionable stick play increased, engulfing players of all backgrounds. The dirty plays, McDonald asserted, is the cause of the fighting and is what needs to be stopped, rather than the fighting itself.

But in spite of those beliefs, which are widespread, the league has continued to make it a goal to penalize fighting. In addition, the league has begun to call more penalties in an effort to produce as much offense as possible, because according to their studies, it’s what the fans want to see. That, McDonald believes, is a big mistake and one the league will pay for in the future.

“Fighting is the one thing that sets the sport apart and makes hockey unique,†he said. “If you watch two great fighters go toe to toe, you can’t help but get the feeling that it’s an art. These guys are extremely tough customers and they definitely serve a purpose out there. I’m not talking about the bench-clearing brawls, even though they are entertaining at times. I’m talking about the one-on-one fight. It changes the entire complexion of the game if done right; it gets an entire team and the fans going all at the same time.â€

Knowing this, McDonald doesn’t really understand why the NHL would attempt to rob the game of one of it’s most entertaining elements.

“Over the years, the league has tried to take that element out of the game because they think the fans don’t like it. Well, they do. That was the thing that filled up buildings in Boston and Philadelphia,†he added. “You couldn’t buy a ticket back then to see the big bad Bruins or the Broad Street Bullies. Sure, they had players like Bobby Orr that the fans loved, but they also had players that were aggressive and would defend each other. That was what the fans came to see.â€

Former NHL enforcer Bob Probert, who racked up 3,300 penalty minutes in a stellar 17-year career feels the same way. Despite scoring 163 goals and being a player who was quite capable of making it in the league without dropping the gloves, Probert is still infamous for the thrashings he has delivered on the ice. To him, fighting will always have a place in hockey, regardless of who’s playing and what the league tries to do to stop it.

“I think that fighting will always be a part of the game. It’s a part of the game that belongs there,†Probert, who scored 29 goals in the 1987-88 season, said. “It keeps players honest and keeps the cheap shots down. People think twice when they know someone will come after you if you get too physical.â€

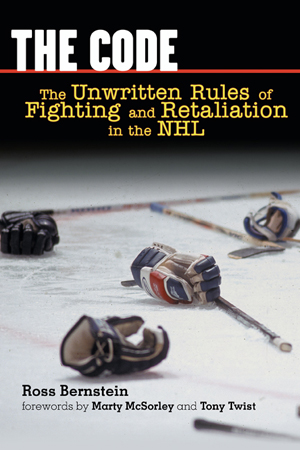

While McDonald and Probert accept and understand that fighting is a part of the game, Minnesota hockey writer Ross Bernstein dedicated a year of his life to finding out exactly why. In the process of interviewing dozens of players during the NHL lockout in 2005, he consistently came across the word “code.†It was during the writing of his book, “The Code: The Unwritten Rules of Fighting and Retaliation in the NHL,†that he began to understand what it was. The unspoken, unwritten rules that most hockey players abide by. “The Code,†as Bernstein put it in his book, is a system devised to protect talented players and ensure every player is responsible for their actions on the ice. While the majority of the athletes on the ice follow “The Code,†there are exceptions, which of course, lead to fisticuffs.

“It’s all about respect,†Bernstein said. “You have to always be accountable for your actions. When you decide to play like a jerk and hit people from behind or take liberties with someone and be disrespectful, you have to be held accountable. In hockey, there are serious consequences for actions like that. Hockey is very unique in the fact that it is allowed to police itself.â€

The players doing the policing, known as enforcers, try to make sure that “The Code†isn’t broken. These are the players that have inspired the creation of websites like HockeyFights.com and HockeyFighters.com in recent years that attract thousands of fans every day. According to Bernstein, enforcers are often the most loved players on their teams. Some hockey enthusiasts believe enforcers play much of a role in their teams’ success, but Bernstein disagrees.

“Fighters, in my opinion, are like kickers and punters in the NFL,†he said. “They’re specialists and without them, you can’t win. Just like the kickers, they don’t get the same amount of respect, because they usually can’t skate as well as the other players. Nevertheless, they’re very important pieces to a championship team.â€

However, while many have voiced their beliefs that there is indeed a place in the game for fighting, citing the nostalgia and history it has, Bernstein also believes that having enforcers to protect teammates makes the game safer.

“Many people don’t understand that in hockey, there are a series of checks and balances,†he said. “If you’re a player that likes to play dirty, your teammates won’t even want you around after a while. The way the code works is if someone isn’t held accountable for their actions and doesn’t ‘show up’ afterwards, his teammates won’t want him on the bench. As barbaric as it may seem, fighting cleans up the game.

“Where I live, the Minnesota Wild have Derek Boogaard as their enforcer. He’s 6-foot-7 and 270 pounds. He’s an animal. Without his presence, you wouldn’t see Marian Gaborik, Brian Rolston or Pavol Demitra scoring goals. If the opposition knows they can take liberties with those guys, they can’t win. Boogaard on your team gives them confidence and lets them get in front of the net and skate without fear of getting whacked.â€

Probert too thinks things would be quite different on the ice if he and his fellow tough guys weren’t around in one way or another.

“There were times when players were going after Steve Yzerman and I had to go after them,†he said. “Sometimes though, there are just times when you look at someone the wrong way and you go at. There’s also the motivation factor, a big hit or a fight can definitely motivate your team and change the game. That’s what my job was.â€

However, many of the leagues top tough guys like Chris Simon and Darren McCarty have had problems keeping up with some of the more talented players over the past few years, leading to an unusual amount of suspensions by the very people who were expected to police the game, many think their existence in the league may be running it’s course.

“What I think is happening is because of the new rule changes, a-la getting rid of the red line, the cutting down on obstructions and the salary cap, the way of the enforcer is slowly, but surely going the way of the dinosaur,†Bernstein said. “I don’t know if a Tony Twist would make it in today’s game. Even Tie Domi also retired very quietly. Guys like that are always the most popular players amongst their teammates, but they’re kind of a luxury that you can’t afford to keep.â€

With the role of the enforcer changing and the league continuing to take steps to eliminate fighting from the game, Bernstein still doesn’t think fighting will stop altogether. Nevertheless, he feels a new kind of player will emerge and take its place.

“I think the agitators are the new wave,†Bernstein said. “In New York, you have a guy like Sean Avery. He’s a perfect example; he can play, he can hit, he’ll fight, he’ll turtle and he’ll draw penalties. He’s the new hybrid. He’s not a big lumbering Snuffaluffagus. He’s not going to take up space and come on the ice like a nuclear bomb when his buttons are pushed and beat the crap out of somebody. I think guys today have to take a regular shift and contribute, kill penalties and even be able to take a penalty shot at the end of a game if they had to.â€

Although Bernstein is a fan of the rough stuff, he feels that the game will continue to have plenty of action even if the enforcers do become extinct.

“I like fighting and I think it serves a purpose, but I’m not a fan of gratuitous fighting you see when a team is down 5-1 and is trying to change the momentum of a meaningless game to sell tickets,†Bernstein said. “I like it when Jarome Ignila drops the gloves in the playoffs when it means something or when a player runs into a goaltender and you have to go. I love seeing the kind of emotion on the ice when you see two non-traditional fighters go.â€

This type of responsibility, which forces hockey players to be accountable for their actions and for a select few to play peace keeper, is what Bernstein believes sets hockey apart from the rest of the sports world and preaches the ultimate team dichotomy and an end result that can’t be found anywhere else.

“Hockey is all about the team, sticking up for each other and growing a playoff beard,†he said. “You aren’t going to find that anywhere else.â€

Despite the thoughts of people like Bernstein, McDonald wonders what will happen if the game continues to be censored the way it has been over the past five years.

“Referee Andy Van Hellemond was once quoted saying, ‘If we take fighting out of the game and the arenas are empty, how do we put them back in?†McDonald said. “I think a lot of cities are at the point where the game isn’t as entertaining as it used to be. If it’s not entertaining to the thousands in the arena and thousands more at home watching, it’s not entertaining. There were many nights at the end of my career when I was driving home where I wondered if it was just me, or was this sport really not entertaining anymore?â€

Leave a Reply