Lots of movies as stunning as Rwanda’s “Matière Grise (Grey Matter)†languish on the festival circuit, but there aren’t many that are as self-aware as this. Its distinct vocabulary of images and bold subject matter guarantee that it won’t be coming to a theater near you, and unless it gets into the Cannes Film Festival after playing at Tribeca, this is one of those movies that’s likely to have doomed itself to obscurity. The only other film as different as this that audiences caught onto was “El Topo,†and that came out during the Nixon administration. Not a good sign.

Lots of movies as stunning as Rwanda’s “Matière Grise (Grey Matter)†languish on the festival circuit, but there aren’t many that are as self-aware as this. Its distinct vocabulary of images and bold subject matter guarantee that it won’t be coming to a theater near you, and unless it gets into the Cannes Film Festival after playing at Tribeca, this is one of those movies that’s likely to have doomed itself to obscurity. The only other film as different as this that audiences caught onto was “El Topo,†and that came out during the Nixon administration. Not a good sign.

Still, the energy behind this film comes from its own acceptance of how unconventional it is. Even one of the characters feels that way: He’s an aspiring filmmaker named Balthazar (Hervé Kimenyi) who can’t get his debut feature “The Cycle of the Cockroach†off the ground because it’s got no budget. After begging a potential backer for funding doesn’t work, Balthazar confides in actress Mary (Natasha Muziramakenga) that he’s bent on making it anyway, damn the expense. When he discusses with her a rape scene involving a cockroach as a metaphor for what women endure, the look on her face clears up any speculation as to why he can’t find an investor.

As he goes through the dialogue alone in his room, we get a glimpse into his imagination to see the film he wants to bring to life, starting with the isolated drama of a madman (Jp Uwayezu). He shares a cell in an asylum with a cockroach he found and held captive in a glass, and until the rape, all we see him do is try to intimidate the bug with incessant hollering. The madman’s existence is as forlorn as his captive’s.

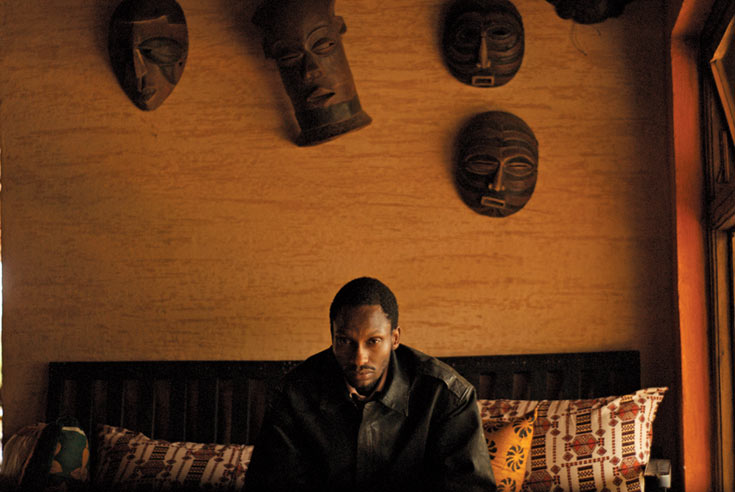

After that begins a different narrative about Yvan (Ramadhan Bizimana) and his sister Justine (Ruth Nirere), who takes care of him because of the post-traumatic-stress disorder he developed following the 1994 genocide. Given that he’s had a helmet on for a pretty long time, and that he insists on leaving a bucket in the bathroom to fill with water and douse the flaming remains of family members in the images that haunt him, Justine concludes that she’ll need to do absolutely anything to help him.

With the exception of Uwayezu’s inconsistent performance, the cast members do an excellent job of fleshing out director Kivu Ruhorahoza’s concept of art as the cause of and answer to whatever ails us. It isn’t as comprehensible as the blockbusters audiences have grown accustomed to, but then again, the human condition hardly ever is.

Leave a Reply