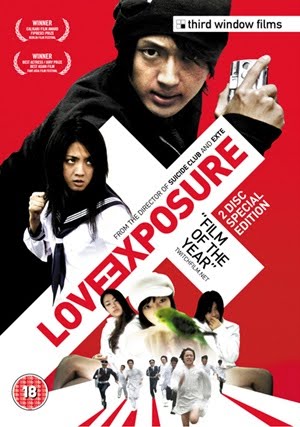

Epic movies- most likely war, royal drama, period pieces. Things like cheap martial arts action, peek-a-panty pervert photography and cross-dressing lesbian clandestine romances, are less likely to make that list. Yet, that, plus more works in Love Exposure, Sion Sono’s four-hour opus on sex and religion.

Epic movies- most likely war, royal drama, period pieces. Things like cheap martial arts action, peek-a-panty pervert photography and cross-dressing lesbian clandestine romances, are less likely to make that list. Yet, that, plus more works in Love Exposure, Sion Sono’s four-hour opus on sex and religion.

The story follows Yu Honda, portrayed by Takahiro Nishijima of J-pop band AAA, a devout Catholic son of a widowed priest. His idyllic life is thrown into chaos when his father Tetsu begins a secret love affair with a new parishioner. The quick collapse of this relationship sends his father into a judgmental, fire and brimstone spell, forcing Yu into daily confession. Lacking any true sins to confess, Yu begins seeking out sins to commit, landing him in the company of three delinquents. This leads him into the world of peak-a-panty photography, a combination of martial arts and cameras to secretly snap pictures of panty shots in public. After all, nothing is a bigger sin than sexual thoughts. The photos enrage his father, but do nothing to arouse Yu.

Only Yu’s Maria, his true love, can give him rise. She arrives in the form of Yoko Ozawa, portrayed by Hikari Mitsushima. A recent runaway from her abuse father, and de-facto adopted daughter of Tetsu’s former lover, she recently dove headlong into Christianity. After assisting her in fending off a gang of hoodlums, Yu and Yoko instantly fall in love. There’s a catch though: Yu was cross-dressing at the time, and Yoko is convinced she has a lesbian love for the mysterious “Miss Scorpion.†The situation only gets more complicated when Tetsu reunites with his lover, turning Yoko and Yu into “siblings.â€

The arrival of Aya, portrayed by Sakura Andou, at Yu’s school brings everything to a head. The sadistic leader of a cult, Aya had been manipulating actions behind the scenes, to drive Yu away from his family and Yoko. After drawing them into the Zero Church, a reference both to Protestant Evangelism and radical Japanese cults like Aum Shinrikyo, the showdown for Yoko’s soul begins.

The acting highlight of this film is the performances of Andou and Mitsushima. On the surface, their characters seem identical, young teenage girls scarred by the abuse of their sexually deranged fathers. But Mitsushima, with her round, angelic face and bright fury, depicts how Yoko has turned that trauma into a righteous rage, proud and impassioned. She is constantly sure of herself, even when she shouldn’t be. Andou, with her creepy smile, borderline vacant stare, and mocking cadences, embodies a mind that re-acted with psychosis. They start at the same place but arrive on different sides of madness.

The cinematography, however, is mixed. The colors are mostly dull and flat; the scenes look like there is a fine bit of smoke in the air, even if there isn’t. The camera work has a lot of jagged, organic movements, like a student film. While this combination works well for the action and peek-a-panty photography sequences, it cheapens the more dramatic scenes. The exception is Yoko’s fiery monologue of Corinthians 13, in which, thankfully, the camera stays still.

However, the film’s refreshingly original take on Catholic guilt and sin makes this film worth the multi-hour investment. Sono depicts people as inherently good- even the delinquents. Evil arises from abuse, religion included. The churches’ demands of repent-ance and confession do not alleviate the sins of the character; they are the cause of those sins. The inherent goodness clashes with original sin, creating guilt. Sono takes this to an almost comical extreme, presenting Yu’s erection as the purest symbol of love and fidelity. Preventing his erection is not a sign of sin defeated; it is the castration of his love. In this way, the title becomes a triple entendre: the exposure of the panties, the exposure of the camera. The exposure of what is truly good.

Leave a Reply