For more than 40 years, women throughout the world have been organizing for gender equality. Of course, this has meant different things to different people. For some, it has meant involvement in electoral politics—getting more women into public office, from school boards to Congress. For others it has meant changing workplace dynamics–challenging sexual harassment on the job and demanding equal pay for work of equal value. Still others have focused on human interactions and have been outspoken in denouncing battering, rape, sexual assault and other crimes that have long served to keep women afraid and powerless. And lastly, feminists have looked at gender itself, and have tried to deconstruct what it means when we call someone male or female.

For more than 40 years, women throughout the world have been organizing for gender equality. Of course, this has meant different things to different people. For some, it has meant involvement in electoral politics—getting more women into public office, from school boards to Congress. For others it has meant changing workplace dynamics–challenging sexual harassment on the job and demanding equal pay for work of equal value. Still others have focused on human interactions and have been outspoken in denouncing battering, rape, sexual assault and other crimes that have long served to keep women afraid and powerless. And lastly, feminists have looked at gender itself, and have tried to deconstruct what it means when we call someone male or female.

Needless to say, despite gains in some areas–abortion remains legal and domestic violence is no longer ignored as a private family matter—women still earn less than men, “rape culture†is a grotesque fact of life, and achieving parity in public life remains a far-off dream. That said, an often overlooked aspect of contemporary feminism has been the changes wrought in men, or at least in those men who truly want to shift gender expectations and be more fully human.

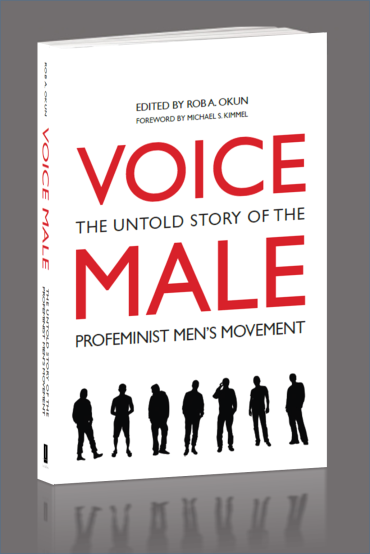

Rob Okun, a psychotherapist and the longtime editor of Voice Male Magazine, celebrates these men in a 140-entry anthology, also called Voice Male. The volume serves as an excellent introduction to the sometimes contradictory, and typically thorny, activism of profeminist men and includes personal essays, research, poems, and polemics that range from raw personal accounts to scholarly commentary. It’s a terrific combination and includes pieces written between 1914 and today. It’s also racially, culturally, and sexually diverse, with articles written by those who identify as gay, straight, bisexual and transgender. What’s more, while most of the material in the collection is written by men, a few women, notably playwright Eve Ensler and journalist Michele Landsberg, are also included.

Among the more provocative entries is The Unbearable Whiteness of Suicide-by-Mass-Murder by Cliff Leek and Michael Kimmel. In it, the authors report that “ninety percent of the shootings at elementary and high schools in the US have been perpetrated by young white men. There is clearly something happening that is not only tied to gender, but also to race…When young men of color experience aggrieved entitlement they may react violently. But the victims of their violence are those whom the shooter believes have wronged him. White men have a somewhat more grandiose purpose; they want to destroy the entire world in some cataclysmic, video game and action movie-inspired apocalypse. Yes, there is mental illness speaking but it is a mental illness speaking with a voice that has a race and gender.â€

While theirs is ultimately a plea for non-violence, they are not alone is questioning the link between aggression and male behavior.

Writer and teacher Jackson Katz notes that “women commit less than one percent of rape. Whether the victims are male or female, men are overwhelmingly the perpetrators.†Given this fact, Katz wonders why rape continues to be called a women’s issue. It’s a good question and is followed by an even better one: What can feminist men do about it?

Paul Kivel of the Oakland Men’s Project, believes that male violence—and stereotypes about “real†men being unemotional, rational and consistently strong–will endure unless men denounce them. “Sexism continues because men collude with other men in perpetuating it,†he writes. “We often actively bond with other men around objectification, sexualization, marginalization or exclusion of others.”

Kivel concludes that the payoff in creating a more egalitarian world will benefit both men and women. This is not a new realization. Indeed, Floyd Dell’s Feminism for Men, penned a century ago, argues that, “the place for men and women is the world. That is their real home.†Dell further notes that while men gain from female subservience, it gives them a false sense of power. “Men are afraid that they will cease to be sultans in monogamic harems,†he wrote. â€But the world doesn’t want sultans. It wants men who can call their souls their own. “

Nowhere is this more blatant than in essays that critique childrearing practices and the limited roles normally assigned to fathers. One of the most powerful pieces is written by Mumia Abu-Jamal, imprisoned on death row, about his forced separation from his progeny. Called Father Hunger, Abu-Jamal recognizes his own pain and compares it to the pain of inmates who were raised without dads, granddads or uncles, or who felt unloved by the males in their lives. It is a sobering and heartrending lament.

Emotional pain is also on display in essays focused on sexual violation, whether by religious leaders, teachers, coaches, family members or trusted friends. Randy Ellison’s Breaking the Silence on Sexual Abuse is an angry and clear-eyed assessment of what is lost in the morass of abuse. First, he reports the extent of the problem: One in six boys and one in three-to-four girls is abused before he or she turns 18. “Remember society’s unspoken code of silence: Innocent until proven guilty. We really don’t want to believe anyone could do that,†he writes. Consequently, Ellison says that prosecution rates are abysmal—only two to three percent of sexual assaults on children are ever punished. “The results,†he continues, “are devastating. A lot of survivors, myself included, feel as though our souls were stolen. My abuse threw me off the track of my life. I thought I would be a minister, but not only could I not pursue that path, I dropped out of college and drifted through several careers and life in general.â€

Voice Male mixes personal reflections like Ellison’s with political prescriptions and practical information—including resources for survivors and those interested in promoting gender justice. This makes it a potent, thought-provoking and insightful introduction to late 20th and early 21st century feminism and an important resource for those wishing to end sexism once and for all.

Voice Male: The Untold Story of the Profeminist Men’s Movement, Edited by Rob Okun, Interlink Books, 2014, 376 pages, $35.

Leave a Reply