Her birth name was Lizzie Douglas [1893-1973] but blues aficionados have long known her as Memphis Minnie, a brash, feisty, independent woman who refused to work in the southern cotton fields and instead sought fame—if not fortune—as a roving singer and guitarist. Musicians as disparate as Chuck Berry, Maria Muldaur, Bonnie Raitt, Big Mama Thornton, Muddy Waters, and Lucinda Williams have touted her influence; likewise, blues historians Beth and Paul Garon, whose recently re-released and expanded 1992 book, Woman With Guitar, aims to push Minnie’s legacy into the 21st century.

Her birth name was Lizzie Douglas [1893-1973] but blues aficionados have long known her as Memphis Minnie, a brash, feisty, independent woman who refused to work in the southern cotton fields and instead sought fame—if not fortune—as a roving singer and guitarist. Musicians as disparate as Chuck Berry, Maria Muldaur, Bonnie Raitt, Big Mama Thornton, Muddy Waters, and Lucinda Williams have touted her influence; likewise, blues historians Beth and Paul Garon, whose recently re-released and expanded 1992 book, Woman With Guitar, aims to push Minnie’s legacy into the 21st century.

While the book is deeply flawed – it is inaccessibly written, unorganized, and their analysis of song lyrics often veers into psychobabble – it is nonetheless a fascinating glimpse into both the music industry and the politics of race, class, and gender in the US of A.

Minnie – the authors speculate that her chosen name may have been an attempt to ride the coattails of two popular early 20th century figures, Minnie the Moocher and Minnie Mouse – was a force of nature. And although little is known about her early years as the oldest daughter of southern sharecroppers, the Garons write that she was clearly intrigued by the vaudeville-style “classic†blues that dominated the industry from 1920 to 1925 or 1926. The Great Depression essentially shut down the music business, they explain, but by the mid-1930s, “country blues†was ascending. Unlike the largely-female musicians of earlier eras, the newly successful up-and-comers “tended to be unsophisticated males who accompanied themselves on acoustic guitars…What happened to the vaudeville blues women was not at all unusual. To hire black men to fill jobs once held by black women was consistent with the sexist practices of the day and upheld the mainstream cultural notions that a woman’s place was in the home, and men were better than women at most jobs, and that it was a man’s role to work for a living for the rest of ‘his’ family.â€

Minnie, however, was not easily discouraged and pooh-poohed this restrictive ideology. Instead, she wrote her own material and elbowed her way into the limelight. Her talent was impressive and after partnering with singer Kansas Joe McCoy, the couple travelled to New York and began recording for Columbia Records. They later worked with Vocalion and Decca.

The two eventually settled in Chicago and became part of the southern exodus of Blacks who were moving to northern and mid-western cities in search of work. There, they performed in dozens of locales and became a hit with the burgeoning African American community. Although the marriage eventually soured, Minnie’s solo career remained stable and she toured the country playing at Saturday night fish fries as well as large urban venues. She continued this routine throughout the 1930s, 40s, and 50s.

Part of Minnie’s appeal, the Garon’s note, rested with her love of innovation and she became one of the first blues performers to play the electric guitar. She was also “regular folk,†and was known to be a hard drinker and savvy gambler “who shot craps like a man.†What’s more, she was nobody’s fool.

Her second marriage to Ernest “Son Joe†Lawlars in 1942 evolved into a successful musical collaboration. Power was shared, although the Garons note that Minnie never ceded control of her music to Lawlar or anyone else. Her reputation as a tough customer prevailed and the Garons write that she often had to fight for recognition, forcing those in her orbit to take her seriously.

Race, however, was a different matter and as an African American female in the Jim Crow south, she was frequently stymied. One anecdote from the text tells the tale: “Minnie, Brownie McGee and Sonny Terry were at a ‘hillbilly concert’ in the Washington, DC area, sometime in the 1940s. They had to sleep in a field since they were barred from the hotel and they were not permitted to eat at the same table as the other, white, entertainers.â€

But even this did not deter the irrepressible Minnie and she missed no opportunity to sing ribald tunes about drinking, love, monogamy, poverty, sex, work, illness, infidelity, and doing what had to be done to survive as a person of color in a racist world. Humor was apparent in Minnie’s lyrics; similarly, sass, spunk, and determination featured prominently.

“Minnie’s act of singing opposed the masculine convention of the silent woman,†the Garons write. She also posited women as more than objects of desire, essentially rolling her eyes at depictions of a “fair sex†that needed men for support and sustenance. In addition, Women with Guitar notes that Minnie sang to, and for, women and girls since they were the primary audience for her music. “Farm women and their children listened to records on the phonograph during the day, while their husbands joined them after work in the fields. Some women listened while sewing,†they report.

This undoubtedly thrilled Minnie and she continued performing until illness made it hard for her to speak, let alone sing. She died on August 6, 1973 and was buried in the tiny town of Walls, Tennessee, where she had spent much of her childhood. For nearly 25 years, the Garons write, her grave was unmarked. That changed thanks to Bonnie Raitt, who, in 1996, provided funds so that a headstone could be erected. The Garons do not tell readers how this came to pass– another of the book’s deficits.

That said, Woman with Guitar showcases an intrepid performer who defied the odds, lived life on her own terms, and refused to accept the status quo, especially when it came to restrictions on women’s agency. She refused to be submissive, meek, or quiet and was unafraid to make demands or get angry. Beth and Paul Garon celebrate Minnie’s bold spirit and are to be credited for introducing her to a whole new generation of potential fans who will likely now hear her on YouTube. Furthermore, their work has raised a slew of questions about American blues women, opening the door to additional research and exploration.

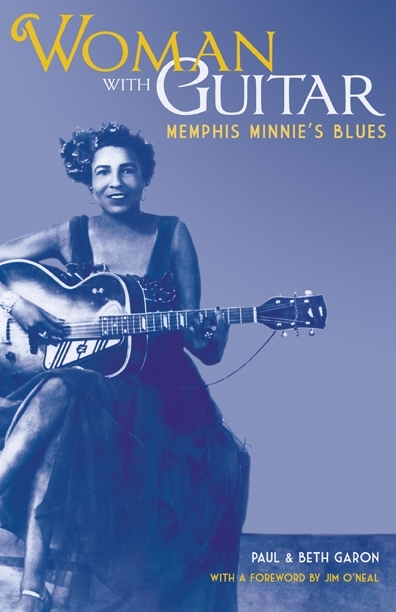

Woman With Guitar: Memphis Minnie’s Blues, by Paul and Beth Garon, Foreword by Jim O’Neal, City Lights Publishers, 408 pages, $18.95 paperback, 2014. [This is a revised and expanded edition of the Garons’ 1992 book of the same name.]

Leave a Reply