George Santiago always wanted to be a professional wrestler. As a kid, he’d scurry to his brown couch in the living room of his home in Borough Park, Brooklyn, and watch the Monday Night Wars every week. His 42-inch tube television often acted up and absorbed Ric Flair-esque chops to maintain a decent picture. He dreamed that one day the TV would show him, after a strong whack, of course, flexing his biceps as thousands of fans cheered his name.

As he got older, his jet-black hair grew past his shoulders, like his childhood heroes, Chris Jericho and The Hardy Boys. At 5-feet-9, 150 pounds, he was smaller than them but made up for it with a daredevil’s passion. As a teenager, he wrestled in backyards, schoolyards and anywhere else he could. His friends watched in awe as he delivered suplexes on the street with reckless abandon. He had no fear. He often laughed or stuck his tongue out before jumping off the top of 10-foot high monkey bars onto his opponents. It didn’t matter if he landed hard on the cement. He was in love.

“I’m still hurting from those bumps,” he said, wincing.

Santiago, now 24, ditched the backyard scene long ago and has spent the last eight years training for his chance at professional wrestling superstardom. He wants to be that larger-than-life guy on the TV.

The Struggle

By some estimates, 2,000 professional wrestlers are bouncing through rings in venues big and small in the United States. Only a couple of hundred work for major operations like the WWE and TNA. The rest strive, for the dream, one, which for most, probably never will come true.

Santiago knows his chances of reaching the big arena will be as difficult as Rey Mysterio bodyslamming The Big Show. But that hasn’t stopped him from trying.

Even the lucky few jump through their own rings of fire. Steady employment is a rarity. A character who flops or a lack of support from a booker can cripple a wrestler’s chances for success after the first trip into the ring.

Relegated to dozens of small independent operations, these indie grapplers risk injury for as little as $25 a match. All have the same hopes as Santiago. Being booked in a match on television is a milestone. Staying with the company long enough to make a living is the goal.

“I’ve dreamed about doing this my entire life,” said Santiago. “Sometimes I think about how my life would be if I didn’t wrestle. But right away, my mind goes back to trying to make this become a reality.”

Review Fix Exclusive- George Santiago Interview-Click to Listen

Away from the glitz and glamor of televised wrestling is a grueling emotional and physical journey. Training is a must for every aspiring pro. The process is a long one, with no guarantees.

“If you’re going to do this, expect to not make much money for a long time, if ever,” said pro wrestling scribe Scott Teal, who has co-written books with everyone from Stan Hansen to Bill DeMott. “I hate to sound so negative, but there’s just not a lot of opportunities in the field right now.”

Even when he was just a teenager scraping in backyards, Santiago knew he couldn’t get far alone. “It’s so much better when you have someone help you,” he said.

Getting Started

Tony and Carrie Santiago knew nothing could dissuade their son from pushing ahead, but were worried about his safety. Tony, a healthcare professional, and Carrie, a manager at a candy shop, wanted to send him somewhere he could train safely. They turned to WWE Hall of Famer Johnny Rodz.

These days, Rodz hangs his black-and-silver boots, the ones he used to stomp everyone from “Fast Draw” Rick McGraw to “Rowdy” Roddy Piper, at the legendary Gleason’s Gym, in the shadow of the Manhattan Bridge in Brooklyn. While Gleason’s is known around the world as an elite, if gritty boxing training center, which spawned the likes of Mike Tyson and Zab Judah and other former champions, the first thing you see once inside the doors is Rodz’s ring.

Santiago walked into the gym for the first time in the spring of 2003 at age 16, looking more like a pro skateboarder, with baggy jeans and long hair, than a wrestling wannabe. But he oozed with enthusiasm and confidence. Before he could perform a roll or flat-back bump, Santiago encountered his first obstacle: Johnny Rodz’s conscience.

“His father told me he wasn’t doing good in school,” Rodz said.

Santiago’s dream had to wait. Rodz sent him home. The teen had much to learn outside the ring.

“For me to even take some of these kids serious, I have to see that they are capable of taking something else serious first,” Rodz said.

Training

Rodz had encountered hundreds of aspiring wrestlers like Santiago over the years, many of whom never bothered to return after getting turned away. But Santiago left determined to prove to Rodz “and his family“ that he wanted this life.

He would have jumped in front of a train if it meant a chance to get in the ring. But Rodz knew that a reckless lust for the sport wasn’t enough. Santiago needed heart. Rodz told him his grades would have to improve. That’s the only way he’d ever dance in Rodzs ring. He told Santiago to come back in a year. Then they’d talk.

Santiago was crushed. Watching the sport on TV made him think about the day Rodz sent him home. But he believed. He focused in school and joined the Franklin Delano Roosevelt High School junior varsity wrestling team. He wasn’t happy about it. The thought of wearing a pair of huge protective earmuffs and a jockstrap and spending most of his time squirming on the floor wasn’t wrestling to him.

Santiago worked after school at a nearby Taco Bell, where for $5.25 an hour, he did everything from cleaning up to working the register to making the food, which he ate a lot of. As he packed on the pounds, he saved every ounce of cash he could. He slowly squirreled away his wrestling school tuition of $2,000, without any financial help from his family.

“My father didn’t think I could do this,” Santiago said. “He didn’t think I was tough enough. That’s why I paid for it myself. He’s supportive now, but I had to do that to prove it to him and everyone else that this was what I wanted to do.”

The constant smell of beef did more than put money in his pocket. The Taco Bell grub helped him put on the added weight he needed to fill out his then-thin frame. His baggy clothes didn’t show it, but in a year, he put on 10 pounds of muscle. With his new body, he learned some basics from his high school wrestling coach. He wasn’t quite ready for the main event at Madison Square Garden, but the experience humbled and hardened him.

“I learned a lot there. You have to know how to protect and position your body properly,” Santiago said. “It’s all about discipline and knowing what is coming next and letting it come to you.”

On March 8, 2004, he strode into Gleason’s Gym, with better grades and a stronger mind and body. Rodz saw a wild young lion ready to be tamed. But that first day, Santiago wasn’t roaring. Far from it. He was bored. He wasn’t allowed to show off any of the moves he did in his backyard. No Neckbreakers. No suplexes. Not even a Snapmare. Instead, he was told to climb through the ropes and get the feel of the ring. That’s not what he wanted. He wanted to fly.

After walking around the ring for a few minutes, he was asked to roll repeatedly. He felt like a sweaty crash test dummy, taking slam after slam from a wrestler who called himself “Starlight.”

“It was weird,” Santiago said. “That’s what he told me to call him, so I did.”

Then he ran the ropes until he had welts across his laterals, and felt as if he were about to vomit in exhaustion. There were no bright lights or busty women cheering for him ringside. Just the smell of his own sweat and the taste of it creeping down his forehead onto his upper lip. He thought about quitting.

“I just said to myself, ‘Can I take a beating like this?'” he recalled. “You hit the mat and it’s not that bad at first, but it takes the air out of you. I just hurt all over and I knew this was just the beginning.

When his father picked him up at Gleason’s that night, Santiago was unusually quiet. His father thought his usually chatty son was tired. He was, but he was also petrified that he wasted his and his parent’s and Rodz’ time. He didn’t know what to say. All he could do was lean his head against the passenger seat and look out the window, with his drenched hair fogging the glass up as they drove along the BQE.

“I worked so hard to get to that point,” he said. “I thought I could do this right away, but after a few bumps, I wasn’t sure if I wanted to do this anymore. I thought I made a big mistake.”

The next morning, sporting fresh bruises, Santiago’s pride was sorer than his body. But he woke up with the thrill of being in the ring, even after getting tossed around by a guy named Starlight. It didn’t matter that he was in pain. He was so close. After all the time at Taco Bell and on the wrestling team, he couldn’t give up. He had to stick it out.

“If I stopped right then, I would have always thought ‘What if?'” he said. “I don’t want to be an average Joe or a normal civilian. I can’t be. This is what I always wanted to do and here it was. The first step was right in front of me. How could I walk away?”

Wrestlers will tell you the first set of bruises are the most painful. The first cut the sport gives you is always the deepest.

“You have to stick it out. You have to want it,” said former WWE superstar James “Little Guido” Maritano, who now serves as a WWE referee. “If you don’t want it, it’s not going to come to you. If you’re waiting for someone to do it for you, it’s certainly not going to happen.”

Review Fix Exclusive- Jamesv”Little Guido” Maritano- Click Here to Listen

The ones who stay the course find themselves constantly challenged. They quickly get in the best shape of their lives. They have to grow up quickly, too, as they learn to navigate the politics of the sport. Santiago shut his mouth and listened to Rodz and the other wrestlers when they spoke, whether the subject was a sleazy promoter or locker-room boasts about bedding groupies “Ring Rats” in wrestler-speak. Santiago put his future in Rodz’s calloused hands.

Rodz acknowledges his methods are unorthodox compared to many other trainers, who, according to him, “just want to make money and will send people into the ring who aren’t ready.” Interviewing his students and even their family beforehand, he lays the questions on. His routine is Kool-Aid free.

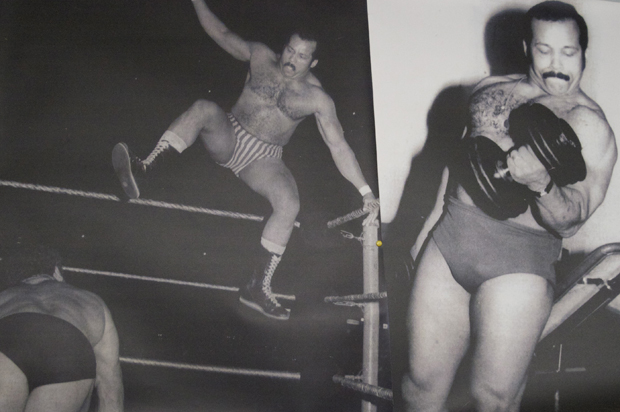

Rodz knows the bitter drink that is professional wrestling all too well. Shining shoes in Chinatown as a teenager, he paid for his own gear just like Santiago. Over 50 years later, Rodz is a proud self-made man. His word, in a world fueled by connections and street credibility, means everything.

While many of the older faces in the sport still hold on to its carnival roots, purposely hiding secrets of the industry, Rodz will share them. He just has to deem prospective recipients of his knowledge worthy. That is the difficult part.

“I ask them all sorts of stuff. I need to see they have the heart. One of my favorite questions is how they’d get to the gym if they didn’t have a car or money for a MetroCard,” Rodz said. “I want people who are dedicated and don’t make excuses.

But Rodz doesn’t sell professional wrestling to anyone who comes in his messy office, plastered with pictures of him with legends of the sport, like Lou Thesz, Superstar Billy Graham and Super Fly Jimmy Snuka. He sells reality.

“If you do this, you will suffer,” he said. “It’s like anything else in life. I got married doing this and I got divorced doing this. I had to shine shoes to do it.

“I ask them what they want to do with their life after wrestling. What will they do if they get seriously hurt and have to rely on their mind? When they tell me they don’t go to school or can’t hold a job? Stuff like that makes me not want to work with them. You have to be smart to succeed in this business and the harder you make it for people to use you and take advantage of you, the longer you’ll last.”

Learning the reality of the professional wrestling industry from Rodz is like being instructed in philosophy by Plato. During his 30 years in the WWE, Rodz was what the business calls a “jobber,” or “enhancement talent.” He rarely won a match. It was his job to make his opponents like Hulk Hogan and Curt Hennig look fierce and formidable in the ring.

“If you wanted to look good, you worked with me,” Rodz said.

As a trainer, he’s able to make his students look as strong as he did his opponents. Over the last 25 years, Rodz has played pivotal roles in the development of some of the top talent of the late 1990s and new century such as Tommy Dreamer, Tazz, the Dudley Boys, Chris Candido and Bill DeMott.

Rodz looks much younger than his 70 years, with his shaved bald-head, neatly trimmed jet-black mustache and a thin gold chain around his neck. He walks around the gym, his students desperate for his occasional nods of approval. Despite a heart condition, he still climbs in the ring sometimes.

“Johnny can still wrestle,” said Santiago. “He’s stronger and faster than you’d expect for a person his age. He works an old-fashioned style, a lot of punches and kicks. Sure, they hurt, but you can go to work the next day. He makes you work smart, though. He calls it “hot potato.” If you’re too stiff, it won’t look good and you’ll accidentally hit the guy. The first time is okay. The second time, they’ll let you know. The third time, you’ll get slapped across your chest. That’s how you learn.”

Rodz, who went from basement rings to Madison Square Garden, also knows one of the best ways to learn is hearing the response of the crowd. The ability to gauge what’s working and what isn’t and make improvements on the fly are the hallmarks of a ring general. Every month or so, Rodz cleans up his ring area, sets up a few hundred gray metal folding chairs, throws a curtain over his door and turns Gleason’s into Wrestlemania for a night. The show attracts hardcore local fans, but it’s mostly family and friends of the talent. About 200 spectators usually show, holding signs for their heel relatives to come and rip in half to get an easy boo from the crowd. Wrestlers’ girlfriends or children often get winks or quick, barely-noticeable nods before the match begins.

By the end of the shows, which can stretch to three hours, the crowd thins to 15 to 20, as each group of family members leaves after their loved one performs. Santiago’s mother, Carrie, always stays till the end.

“She loves it,” Santiago said. “She screams the loudest.”

For some of Rodz charges, it’s the largest venue they’ll ever play. The monthly shows, presented as World of Unpredictable Wrestling, has champions, fan favorites and heels just like every big company. The exposure isn’t the same, though the matches often are recorded and posted on YouTube. The now six feet tall and shorter-haired Santiago, who weighs around 185 pounds, was even WUW champion for a short while.

“It was cool that Johnny had that kind of faith in me,” he said.

Every one of the superstars Rodz trained over the years has wrestled in Gleason’s, before slowly moving onto bingo halls and crusty school gyms. They’ve all squeezed into cars for trips across state lines for matches. They’ve all slept in dirty motels for the night. They’ve all held titles at small promotions. They’ve all waved to Mom in the front row.

Lessons

The smart ones learn the most important lesson early- the need to send fans home happy. That comes with the pressure to outdo your last match every time you step into the ring.

The goal is to stand out, to make a connection with the fans. Wrestlers use different moves or the same moves in different ways. They become engrossed in their character. It becomes a part of them. The act is constantly fine-tuned. If something doesn’t work, try something different. A cheer is gold. A boo, unless called for, means whatever spurred it is banished from of the bag of tricks.

Unlike most other professions, being injured or sick is no reason to miss a match. Or put on a mediocre show. Admitting injury or exhaustion or even complaining is almost a badge of shame.

“I’ve had people tell me they needed time away from this and I thought they were crazy,” said former NWA Canada Champion Scott “Scotty Mac” Schnurr, 32. “When everything in the world is screwed up, I know that this can make me happy and this is where I need to be. When the crowd screams your name, it makes everything feel, at least for a little while, so much less important.”

Review Fix Exclusive: Scotty Mac Interview-Click Here to Listen

Santiago doesn’t show his friends his welts anymore. He goes to the gym every day and takes care of his body. He’s been relatively injury-free. He gets stronger every day. But he’s still got work to do.

Santiago’s in-ring repertoire is solid. He uses the Boston Crab and the Tiger Bomb as his signature holds. But he’s still in search of a gimmick, something to get him on the good side with fans. Away from the ring, he’s bubbly with a warm smile and makes friends easily. He lives at home with his parents while he trains. Between matches, Santiago works the register part-time at Hard Rock Cafe in Times Square and is studying at the Borough of Manhattan Community College for a degree in physical education. Teaching gym is his backup plan- one he hopes he’ll never have to tap.

“People have asked me all the time why I do this and I really don’t know the answer,” Santiago said. “I’ve always wanted to be Intercontinental Champion and to wrestle in the WWE. I’d do anything to one day get there. I love the response from the crowd. When they cheer you, it’s a great feeling. It’s a rush. When they boo you, it’s cool too, especially when that’s what you want from them.”

From Mexico to Brooklyn and Back Again

Like Santiago, Jorge Kebrada grew up in Brooklyn dreaming of becoming a pro wrestler. He begged his parents to send him to a training school. They suggested he try boxing instead. He arrived at age 15 at Gleason’s and was a knot away from lacing up the gloves when he noticed one of the rings wasn’t like the others.

“I saw a ring with three-ring ropes, not four. I knew right away it was a wrestling ring,” said Kebrada. “A few minutes later, I met Johnny Rodz and after a few hours, everything was set. It was one of the greatest moments of my life.”

Born in Mexico and raised in Brooklyn, the 20-year-old Kebrada is a walking duality. Kebrada incorporates his Mexican heritage and U.S. upbringing into his career as the masked luchador Eclipse Beltran. Combining the high-flying moves his countrymen have made famous with the fast-paced and stiff American style Rodz taught him makes Kebrada unique. In five years, he has wrestled in various independent promotions across the country.

But, in a twist out of a wrestling storyline, Beltran recently stopped training with Rodz and moved back to Mexico to live his fantasy of performing in the same arenas he marveled at as a child glued to Telemundo. He hasn’t been able to catch on with a major promotion there. Like Santiago, he has all the moves but is still working on his character. He’s not discouraged.

“After every match, everything is sore. You get bumps and bruises, but that’s part of the game. Plus, once your music hits and you walk to the ring, all your pain goes away. It’s that type of rush. You forget about everything,” Kebrada said. “Sometimes it comes to my mind, ‘why I would do this to myself for other people’s amusement? I try not to think about it like that, though. My heart is always pumping knowing that I can do this because I’ve wanted to do it since I was five. This is what I wanted. This is really big for me.”

Indie promoters use wrestlers’ willingness to do whatever it takes to get ahead to their advantage. They don’t know who is going to be the next superstar. Fans are fickle. Promoters preach the perception of perfection. Their wrestlers perform at a frenetic pace to satisfy the crowd and increase their odds of moving up. Money is everything.

“It’s not about how many flips you can do or who you’re married to,” said former WWE wrestler Michael Tarver. “If you can’t draw money, or they don’t think you can, you won’t work anywhere.”

Promoters don’t quite put it that way.

“Everyone pays their dues in different ways,” said Gabe Sapolsky, vice president of Dragon Gate USA and founder of Evolve, two young independent promotions in the Northeast. “You have to make yourself valuable. Bookers want to know what you can do for them. When I started, there wasn’t anything I wouldn’t do. You have to be marketable and be able to add something to a promotion.”

Survival in the business is more about brains than brawn. Most of the time, the indie guys make decisions very quickly. They’ll wrestle almost anywhere, against anybody to keep getting work. The situations can get dangerous.

When Kebrada was 17 and enjoying his first taste of success, getting booked in matches all over the Northeast, he was put up against a backyard wrestler in New Jersey. The guy was green and known for taking risks. Beltran was not interested in letting this clown mess with his livelihood.

“We started planning our match. After five minutes of him talking, I could tell he was a backyard guy,” he said. “He wanted to do all these elaborate moves, all at once. It made no sense. The bottom line is good wrestling looks real and doesn’t hurt you.”

Some wrestlers ignore their instincts. After all, this could be the match that gets them noticed. There could be an agent in the crowd. But that night in New Jersey, Kebrada put his safety first.

“I really wanted to see his gear. He came back like 10 minutes later and I saw he was wearing Nikes and basketball shorts to the ring. There was no way I was going to do half the things he wanted to do after that,” Kebrada remembered. “He was clearly insulted, but we ended up doing a pretty standard match. Even that wasn’t too good. He wasn’t a good worker. Everything looked clumsy. However, no one got hurt. I was able to go home in one piece. That’s what it’s all about. One bad match with a backyard wrestler isn’t going to kill me. Having him do a move the wrong way will.”

Kebrada got paid $50 that night. He doesn’t make quite that much per match in Mexico, these days. The most Santiago has earned in a night is $125, despite working all over the country and in the famous ECW arena in Philadelphia. The money often goes right back into training, masks, boots, tights, food, travel and hotels.

The drive to move up the card motivates the wrestlers. The name of the game is attracting attention, even in church basements, at block parties and abandoned bingo halls. These are the places where success stories and failures begin.

When Santiago first started training, he managed to sneak backstage into an independent company’s show at a Bensonhurst church. After lingering in the back for a few hours, he peeked through the curtain and watched the main event. He watched in awe as the 5-foot-8, 170-pounder, with a shaved head and a Bruce Lee physique, landed vicious kicks and punishing submission holds on his opponent. Santiago saw the response from the crowd for the wrestler who went by the handle Low-Ki. This was the sound he wanted to hear from the audience when he performed. Those cheers, he promised himself, would be his one day in Madison Square Garden.

“Low-Ki is an amazing athlete,” said Santiago. “Watching him in person, you see how good he is. He’s definitely dedicated. The tapes I used to watch him on back in the day don’t do him justice in person.”

An Indie Legend

Low-Ki, AKA Brandon Silvestri, is respected by both his peers and cult-like fans. Like Santiago and Kebrada, he watched the sport as a kid and grew to admire the people he saw in the ring. He’s entered a league that Santiago and Kebrada dream of, landing in the WWE in 2010. But even his ample skills didn’t keep him there for long. He’s now on the outside looking in at the success he briefly tasted.

He began training at a Brooklyn church at 17 and within four years, every professional wrestling magazine listed him as one of the top independent wrestlers in the world. Still, he’s been unable to stick with a major promotion for an extended period.

Silvestri tells every aspiring professional wrestler he meets to go to college. He didn’t. His fate is controlled by forces that see him as an instrument- one that either drives viewers to the television or away from it. Because of his modest build, many larger promoters see him as a risk. They want someone who will immediately draw intrigue. They don’t want a Silvestri, who needs time to show how talented he really is.

“It’s all about how you promote yourself now,” said Santiago. “I wish it was like the way it used to be where a guy could go out and perform for people and get the credit he deserved. It’s all about finding a gimmick now.”

If professional wrestlers were judged merely by their ability in the ring, Silvestri likely would be one of the industry’s kings. But professional wrestling is all about the spectacle. Acting skills and charisma are crucial.

Many fans prefer the soap opera-like storylines over the wrestling. Silvestri sees professional wrestling as more than cheap drama. It’s an art form. Each kick, punch, top-rope maneuver or grapple is a way to tell a story.

“I’ve never talked about what I wanted to do in the ring. That’s not what my character does. I just do it,” he said. I go out there and prove that I can hang with the stars of a company in the ring and even surpass them. I try to gain the audiences’ respect that way.

“You only have one chance to make a first impression. I go out there every night and perform like they’ve never seen me. I try and make sure they know who I am by the end of the match. I like to take people on a journey. It’s a challenge and an opportunity to develop a relationship with people.”

His dedication wasn’t enough to launch him to superstar status. He said he asked to be released from his once-dream WWE deal in late 2010 because he believed he wasn’t being given enough of a chance to connect with audiences. A few months later he was back in his old stomping grounds, TNA, the second largest promotion in the U.S. There, he wrestled two stellar matches, one on television and the other on pay per view, before going back to where his career started – the independent circuit.

He still loves the sport. Too bad it’s incapable of loving him back.

Behind the pyrotechnics, loud music, beautiful women and fantastical storylines, Silvestri sees pro wrestling as a career that demands constant sacrifice- a lifestyle most wannabes can’t handle.

“When I went full time in 2003, I started spending much less time with my family and the core of people I keep close to me,” said Silvestri. “That does take its toll on you, especially when you enjoy having them around. It messes with you. I’ve spent long periods of time overseas and that hurts your relationships with your family, friends and significant other. It’s the nature of what we do, though. It’s something you have to accept and work with if you want to make it.”

The career has afforded him a journey around the world as various characters – Low-Ki, Senshi and Kaval, with companies like Ring of Honor, New Japan Pro Wrestling, Total Non-Stop Action and World Wrestling Entertainment. That adventure is what Santiago and Kebrada train for every day.

Trying to Make It

“It’s always on my mind,” said Santiago. “When I’m at school, I’m thinking about what I could do in a match. When I’m at work, I thought about how I could get the crowd going. My co-workers will catch me in a daze and ask me what I was thinking about and I’ll make something up. But it’s always wrestling.”

In his daydreams, Santiago thinks about new moves to try out in the ring, reaching back to matches he saw on TV as a child, hoping to put twists on old favorites. He also auditions catchphrases in his mind and finds himself gravitating to the bathroom mirror to spout them aloud, complete with matching facial expressions ranging from evil grins to feigned shock. He’s striving to develop a character who can connect with fans.

Silvestri’s character didn’t draw big with the WWE audience, but it is an inextricable part of him. “Call me Ki,” he replies when someone addresses him as Mr. Silvestri. Schnurr works part-time as a bartender and the customers call him Scotty Mac. Most of them, Schnurr said, don’t know his real name. Even on the schedule behind the bar, he’s listed as Scotty Mac.

“I’ve struggled with it,” he said. “I am somewhat similar to my wrestling character outside the ring and it hasn’t been the most positive thing for my personal life. But that’s the way it’s gone. It’s what makes me happy. The wrestling world is a lot more fun than the real world.”

As he strives to find his place in the wrestling arena, Santiago is determined to keep one booted foot planted in the real world and not get swept away by a ring persona. “I see guys who just start training and they want to be called by their character’s names,” Santiago said. “They are complete marks for themselves. I’m just George. Some people call me Santi in the gym and that’s fine, but I’ll always be George.”

It’s not easy being just George in a world that spins on embellishment and artifice. Promoters lie about their performers’ heights, weight- even the size of ladders they jump off. Wrestlers are taught to take their own character traits and blow them out of proportion, inside and outside the ring. The fans arrive at arenas or turn on their TVs with outsized expectations.

“It’s a part of the spectacle,” said Schnurr. “When people know it’s staged, you do different things to try and maintain that suspension of disbelief. Sometimes we even say there are more people in the arena than there really are.”

The Hype

Many pro wrestlers get lost in the hype they help create. They are essentially fans who have dedicated themselves to the craft. At the start of every episode of WWE’s Monday Night Raw, announcer Michael Cole declares the show is television’s longest-running episodic program. Pro wrestlers don’t see that. They see a battle between good and evil, a gladiatorial contest that will be remembered for decades by thousands of spectators, even if the ending is predetermined.

“I think every pro wrestler has to make the decision if they are going to do this for their own enjoyment or to make a living,” Schnurr said. “It was something I wasn’t conscious of early on and you get to the point where you see this as a business and you begin to see things differently.”

Most professional wrestlers aren’t in love with the business but adore the rush they get in the ring. The child who gets hooked on the living room couch never leaves. He’s always there. He cheers every Front-Face Lock and Abdominal Stretch and leaps from the couch, arms raised in victory, with every three-count.

“It’s hard at first because you’re just so happy to be doing it,” Santiago said. “But after a while, you realize that it’s entertainment. It’s an illusion. We work very hard to make people happy and we have goals. But at the same time, you have to take care of yourself so you can continue. I’m at the point now where I know what I have to do to succeed.

“People annoy me sometimes when they ask me if it’s fake or if I take steroids, but they don’t understand. I don’t take steroids, but wrestling is real.”

Leave a Reply