Review Fix chats with film restorer Eric Grayson, who discusses his role in the New Blu-ray edition of the silent film “Little Orphant Annie.†Breakdown the restoration process and why the film is an important one, Grayson believes it’s a silent classic and one that plays a huge role in film history.

Review Fix chats with film restorer Eric Grayson, who discusses his role in the New Blu-ray edition of the silent film “Little Orphant Annie.†Breakdown the restoration process and why the film is an important one, Grayson believes it’s a silent classic and one that plays a huge role in film history.

For more on the film, Click Here.

Review Fix: How did you get involved with this film?

Eric Grayson: I had a friend who had a rotting nitrate of the film, and I wanted to see it get preserved. I was aware that all the video copies on the market were cut severely. There was an opportunity to get the film preserved in 2016, which was the 100th anniversary of James Whitcomb Riley’s death, and I jumped on it. I knew that if I didn’t get it preserved, then it would never happen. I had no idea how the film would turn out. Every version I’d seen made no sense and had glaring discontinuities, but the skeleton of an interesting film was there, so I had faith in it. I’m a sucker for a lost cause and an unusual film, and this fit the bill. It was a real mess in almost every way, and it will never look like “mint condition” again, but it looks awfully good considering the material that was left on it.

Review Fix: What makes this film special?

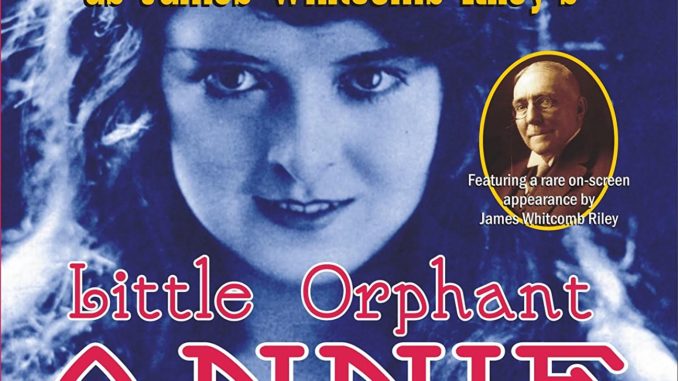

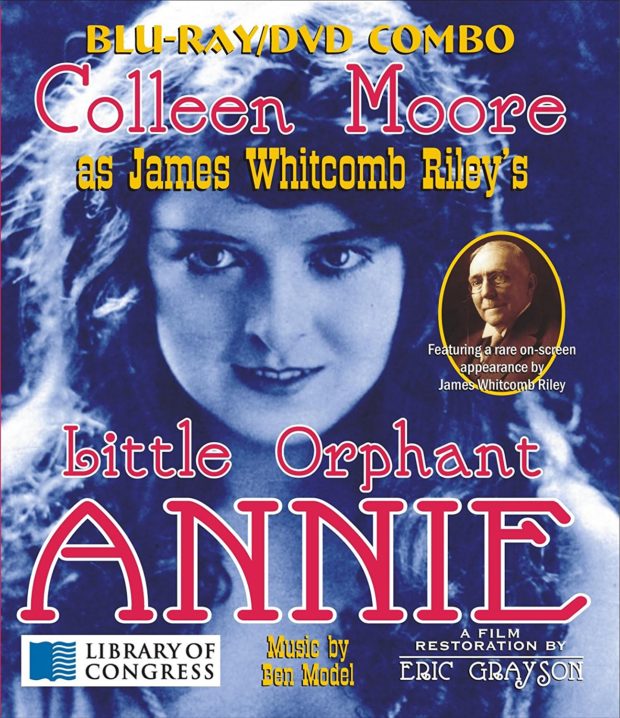

Grayson: It’s the oldest surviving Colleen Moore film. It’s an early film by Charles Stumar, director of photography for The Mummy and many Universal Horrors. The poet James Whitcomb Riley appears in the movie for one of the only times he was ever on camera. It’s very unusual to have such extensive special effects and camera motion this early.

Review Fix: What makes your version unique?

Grayson: All of the surviving prints were out of order and they were all cut or censored. I went through five different prints and assembled the most complete version possible. The tints were also restored based on an unusable 35mm print. Little Orphant Annie had extensive tinting. Almost every shot was a different color. This was done for dramatic effect at the time, and it had not been preserved that way. It actually plays a part in the story: when Annie has a little fantasy trip, the tinting turns blue. That hasn’t been seen in any print since 1926. Of course, this version also has a great score by Ben Model, a commentary by Colleen Moore’s biographer Jeff Codori, and a separate commentary by yours truly discussing a little more of the history of the film and how it was reconstructed.

Review Fix: Bottom line, why must someone watch this?

Grayson: Well, if you’re someone who thinks that cinema started with The Godfather or Star Wars, you shouldn’t watch it. You’ll be disappointed. However, if you’re someone who likes to sample films from the various ages of cinema, then this is for you. It’s ahead of its time in narrative construction, very ahead of its time for effects, and it’s a cute little story. It makes you understand why Colleen Moore became an international star a few years later.

Review Fix: Why are silent films still important?

Grayson: People sometimes think silent films are dull, slow, or stagey, with bad-looking images. That’s not true. Silent films are simply made using a different style, a different rhythm of cutting, a different kind of acting. I think it gives us insight as to how powerful motion pictures are, and how styles evolve and change. When I restored The King of the Kongo a few years ago, I cut a trailer for it in modern style with the black fadeouts and drum music. Kongo could work in a modern style, but I think Annie is the kind of film that couldn’t really be made as a talkie. I think it would be too silly and too “out there,” and people would laugh.

Without dialogue, it has an other-worldliness that suits the story. I don’t want us to lose the pure visual language that was used in silents. It’s not hammy or overdone… it’s just different.

Review Fix: What’s next for you?

Review Fix: What’s next for you?

Grayson: I’ve just finished a restoration of the Milan High School films from 1954. If you want an odd change of pace, this is it. The high school in tiny Milan Indiana came to me with these severely deteriorated game films. This was a legendary David vs. Goliath matchup that was the inspiration for the movie Hoosiers (1986). The films were nearly shot when I got them, but they were saved in the nick of time. I’m also considering restorations of Tod Browning’s The White Tiger (1923), Colleen Moore’s Ella Cinders (1926) and several Willis O’Brien animated films (he was the guy who did the special effects for King Kong in 1933). I can only suggest that people either follow me on Facebook or stay tuned for the next Kickstarter campaign. I’m not sure when things will happen.

Review Fix: Who are you and why did you make a blu-ray?

Grayson: I’m a freelance film historian. I mostly do live shows with real movie projectors and film. Sometimes, people come to me with projects that just have to be done, usually that are beneath the notice of the major archives. The archives are great! I love them, and they do a service to the world that I can’t do. However, they can’t preserve everything, and sometimes I can raise funding and awareness when they can’t. I restored The King of the Kongo (1929), which was the first sound movie serial, from fragile sound discs and an old print, the first time the sound had been reunited with picture since 1929. That got a number of other people interested in having me do restorations on other films. I specialize in silents and early sound pictures, but I also love vintage Technicolor.

I made a blu-ray because I needed to do that in order to preserve Little Orphant Annie. Despite that fact that I knew it had to be preserved on film, I could hardly ask people to fund that when they wanted to see it in their living rooms. I funded it with a Kickstarter project and the result was this blu-ray. I knew that none of the “big boys” like Kino or Flicker Alley would want to release this, so I did it myself. I’m sort of a maverick that way.

Leave a Reply