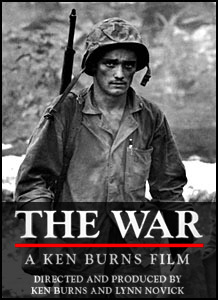

Documentaries like Ken Burns’ “The War†are the reason why we watch television – for material that can enlighten just as easily as it can entertain. Like the director’s last three films – “The Civil War,†“Baseball†and “Jazz†– “The War†defines America with its own past and suggests that a nation can be judged by the history it leaves behind. Burns trusts his carefully chosen words and images from World War II to speak for themselves, avoiding dramatic puffery that would’ve been distracting and dumb. The result is a large and exceptional PBS event in seven parts, which teaches us that what we think of as “the last great war†may’ve been one of the worst.

Documentaries like Ken Burns’ “The War†are the reason why we watch television – for material that can enlighten just as easily as it can entertain. Like the director’s last three films – “The Civil War,†“Baseball†and “Jazz†– “The War†defines America with its own past and suggests that a nation can be judged by the history it leaves behind. Burns trusts his carefully chosen words and images from World War II to speak for themselves, avoiding dramatic puffery that would’ve been distracting and dumb. The result is a large and exceptional PBS event in seven parts, which teaches us that what we think of as “the last great war†may’ve been one of the worst.

The director’s latest epic is also one of his shortest, with a 15-hour running time that’s just a few episodes shy of “Baseball†(18 hours) and “Jazz†(19). Burns is not ashamed to point out its shortcomings in the written introduction, which mentions “thousands of places†that were “too many for any one accounting.†Still, less is more: The early reviews for “Jazz†had problems with the way it rushed everything from 1961 on, reducing the era’s biggest steps to cultural footnotes. “The War†is more thoughtful, more revealing and even more controversial, conjuring outcries from American Indian and Latino veterans to include their stories before it was finished. Burns made room for the edits and is happy with the additions, but told The New York Times that their unkind omission in the rough cut was “the most painful chapter in my professional life, without a doubt.â€

It won’t do any good to describe “The War†in terms of names and dates, since its delivery is crucial to understanding the material. Burns’s approach is just as essential as his trademark photos and letters, which support his films rather than simply complementing them. His are the only documentaries I can think of where people survive in pictures instead of just being frozen in them. Some pictures even suggest movement: Montages of unbalanced shots give the battle scenes a final, frantic layer. They manage to hold up more gracefully than the miles of weathered newsreel footage, compromised by blackheads and pinstripes.

While the facts tell their own story, about 40 veterans tell theirs in what are probably the best interviews Burns has ever done: Some are sourly amused, others openly weep. But does he need to record these stories when there’s already an abundance of other accounts? Absolutely – their stories are what inspire him the most, especially because of recent statistics that mention about 1,000 World War II veterans dying every day.

I’m reminded of what Burns observed in “The Civil War†about Alexander Gardner, the man who shot the famous photo of Honest Abe in 1865. It was processed on a glass negative, which was damaged and cracked. Gardner noticed but wouldn’t bother to have it redone, because there would always be plenty of time to take another picture of President Lincoln.

Leave a Reply