Until Western audiences discovered him in the early ‘70s, Yasujiro Ozu was the best director America had never heard of. He died about a decade before in 1963, and despite having directed over 50 films, the handful that made it out of his native Japan didn’t get any farther than Europe. It wasn’t as if Americans hadn’t caught on to world cinema – they had, in fact, turned into what critic Stanley Kauffmann called “The Film Generation,†which regarded names like Michelangelo Antonioni, Roman Polanski and François Truffaut as visionaries. Even Japan’s other breakthrough director, Akira Kurosawa, managed to gain a following.

Until Western audiences discovered him in the early ‘70s, Yasujiro Ozu was the best director America had never heard of. He died about a decade before in 1963, and despite having directed over 50 films, the handful that made it out of his native Japan didn’t get any farther than Europe. It wasn’t as if Americans hadn’t caught on to world cinema – they had, in fact, turned into what critic Stanley Kauffmann called “The Film Generation,†which regarded names like Michelangelo Antonioni, Roman Polanski and François Truffaut as visionaries. Even Japan’s other breakthrough director, Akira Kurosawa, managed to gain a following.

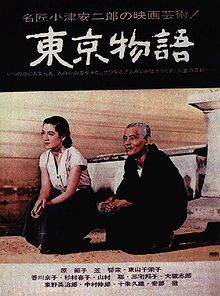

Cinephiles now consider Ozu’s movies essential viewing, but it was 1953’s “Tokyo Story†that put him on the map. The New York Times and New York magazine recommended it when it turned up at the New Yorker Theater in 1972, around the time Paul Schrader’s book “Transcendental Style in Film†added to the Ozu mythos. Eventually, other movie lovers took notice – when the British Film Institute invited critics to list the 10 greatest movies of all time in 1992, “Tokyo Story†ended up at number three. You can find out why during a two-week engagement that kicks off today at IFC Center in New York.

Ken Mogg, who runs The MacGuffin, an academic journal dealing with the work of Alfred Hitchcock, said “Tokyo Story†has an insight to it that makes it one of his favorite films. “Ozu wants to emphasize the essential and the recurring, as these comprise the lasting fabric of a life,†he said. “It’s about knowing one’s limitations, especially as one grows old; appreciating one’s family and wider circle; accepting both joys and disappointments; seeing the universal in the particular or the localized.â€

At the center of “Tokyo Story†is an old couple from a Japanese suburb with children living in Tokyo, whose routines get in the way of bonding when the couple visits. After the vacation is over and the children send their parents home, their mother develops a terminal illness that brings them out to be by her bedside.

While this is dramatic enough to hold down a feature-length film, Mogg said the movie’s greatness isn’t in its story. “It’s in the repetition and the unhurried pacing and the detached camera positions,†he said. “Donald Richie, a great authority on Japanese cinema, used the aesthetic term ‘mono no aware,’ meaning ‘sense of transitoriness, but without undue sadness.’ To see the transitoriness of things and the essence behind them – that’s an Ozu message.â€

Ozu has messages that are less cryptic, though. Mark Schilling, The Japan Times’ senior film critic, said that what makes “Tokyo Story†so accessible is the way it approaches the human condition.

“The film deals with universals such as aging and loss,†Schilling said, “the relationship between parents and children, the selfishness and selflessness that coexist in the human heart in direct but elegant ways that may be grounded in Japanese culture, but are not limited by it.â€

Of course, it helped to have a filmmaker onboard who knew what he was doing. “In the hands of another director, ‘Tokyo Story’ could have been an ordinary melodrama,†Schilling said. “Ozu’s distinctive shot compositions and editing rhythms create a sense of harmony and transparency that raise the film beyond the particulars of its time and place, while making us understand the characters as we do our friends, spouses, relatives or selves.â€

Ozu made “Tokyo Story†in the last years of his life, although other career highs like “Floating Weeds†and “An Autumn Afternoon†were on the horizon. He might not have gotten the attention he deserved during his lifetime, but what he left behind ensured his immortality.

This article originally appeared on AllMediaNY.com

Leave a Reply