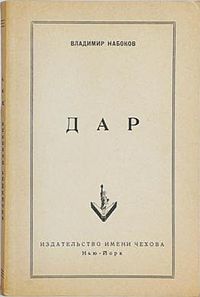

Translated into English as The Gift, the title of the last novel Vladimir Nabokov wrote in his native tongue preserves its Russian name’s double meaning. In the first sense, the book is the author’s last present to his Russian readership. The second one refers to the protagonist’s, Fyodor’s, creative talent. As he often does in his novels, Nabokov blends together his main character’s “real” life and fiction, leaving the readers with a brain-stimulating task of distinguishing one from another. This becomes quite a challenge with 366 pages of dense prose, in which the protagonist’s thoughts matter more than events.

Translated into English as The Gift, the title of the last novel Vladimir Nabokov wrote in his native tongue preserves its Russian name’s double meaning. In the first sense, the book is the author’s last present to his Russian readership. The second one refers to the protagonist’s, Fyodor’s, creative talent. As he often does in his novels, Nabokov blends together his main character’s “real” life and fiction, leaving the readers with a brain-stimulating task of distinguishing one from another. This becomes quite a challenge with 366 pages of dense prose, in which the protagonist’s thoughts matter more than events.

The Gift is, indeed, not for plot or mystery lovers; its artistic value lies in its language and in the way the author plays with the traditional novel form. We can call it a book primarily about writing a book, although it does tell a story about love, coincidences, the life of Russian émigrés in Europe, and most importantly, the journey of a young man in the process of becoming a writer. The Gift is also each reader’s own expedition with surprises waiting at every corner.

The circumstances in which Fyodor develops are somewhat similar to Nabokov’s own life. Both came from a wealthy noble family and lost everything with the revolution, including their homeland, to where they are not allowed to return. Moreover, as Fyodor notes, the Russia he grew up in no longer exists; the new Soviet state that replaced it has little in common with what the young man remembers his country of birth to be like. Despite the obvious similarities, the reader should not be carried away. Nabokov warns us in the introduction to the novel, “I had been living in Berlin since 1922, thus synchronously with the young man of this book; but neither this fact, nor my sharing some of his interests, such as literature and lepidoptera, should make one… identify the designer with the design.” His characters are often developed from the mixture of his personal memories and imagination, which is the case with the protagonist of The Gift.

Even though the novel tells us his story, we see little of Fyodor’s life. We learn that he has published a book of poetry about his childhood. Only 51 out of 500 copies, printed at his own expense, have been sold. Making a living as a private English tutor and a newspaper writer, Fyodor always lacks money. His mother lives in Paris. His sister, Tanya, has recently got married and gone to Belgium for some time with her husband, whom Fyodor has never met. The protagonist lives alone in Berlin, and he has few friends. If we were to write Fyodor’s biography, we would hardly fill a page.

On the other hand, we get to read what Fyodor writes. The novel presents the idea that the book created in the author’s mind, even though not yet written down, already exists. Thus, we encounter multiple stories within The Gift, one of which Fyodor gets published. In the meantime, we watch the protagonist develop from a mediocre poet into a talented novelist.

Telling the story of this transformation, Nabokov often switches from third to first person, and vise versa. As he erases the boundary between the author and the character, it becomes unclear who tells Fyodor’s story. Such sudden point-of-view switches do not, however, confuse or frustrate the reader. Surprisingly, they seem natural and logical.

By the same token, Nabokov toys with literary genres. Lines of embedded poetry often hide within Fyodor’s prose, and on the contrary, blank verse expresses Marxist ideas for the sake of making them “less boring.†Also, the biography of the Russian writer, Nikolay Chernyshevski, written by Fyodor, ends with the information about its protagonist’s birth and begins with what Fyodor calls “a sonnet,†two three-line stanzas. Two quatrains that start the sonnet conclude the biography, thus closing the circle. Likewise, some scenes in The Gift seem to the reader irrelevant until another moment in the book reveals their significance. This makes Nabokov’s work worth reading, at least, twice in order to fully appreciate and understand it.

It is often hard to distinguish “reality†(the word that should always be enclosed in quotation marks when talking about Nabokov) and Fyodor’s fantasy. He carries on imaginary conversations. When writing his father’s biography, he visualizes their joint travels, even though they never went anywhere together. Fyodor’s main talent is, therefore, the ability to think something up and understand other people’s thoughts and feelings. For example, visiting his friend, Alexander Chernyshevski, he imagines his host to envision the ghost of his son, Yasha. The idea “that any soul may be yours, if you find and follow its undulations†also appears in Nabokov’s first English-language novel, The Real Life of Sebastian Knight.

Besides the fact that Fyodor’s writing takes up most of the novel, we can also see how much he values his creative work from the scene in which, immersed in writing the biography of Chernyshevski, Fyodor forgets to go to the masked ball he was supposed to attend together with his beloved, Zina Mertz. Aware of how much his presence at the party meant to Zina, his sweetheart and muse, he dismisses the matter as “a fine mess.†Clearly, no woman will ever possess Fyodor as fully as writing does.

The love story is just as important in The Gift as Fyodor’s literary journey. The fate arranges their meeting through a series of coincidences. Fyodor misses the majority of the chances and takes advantage of the least probable one, seduced by the sight of the dress that did not even belong to Zina. The theme of fate is one of Nabokov’s favorite ones, particularly, in his most acclaimed novel, Lolita, in which destiny brings Humbert Humbert, against his will, to the house where he meets the love of his life, Dolores Haze.

In this sense, reading The Gift serves us as a clue to Nabokov’s other literary works. Specifically, the fact that he calls himself in the writer’s note, “On a Book Entitled Lolita,†“the kind of author who in starting to work on a book has no other purpose than to get rid of that book,†brings us right back to the idea of The Gift that a story’s existence begins the moment one contemplates writing it.

It is important to point out that, being Nabokov’s last novel written in Russian, The Gift contains a lot of references (for instance, to his favorite writer, Alexander Pushkin) and expresses, through Fyodor, the author’s view on various prominent figures in Russian literature.

At the same time, we get a slice of life of an excluded from his homeland émigré writer, doomed to limited readership, which was one of the reasons why Nabokov himself decided to switch to English. This allows us to perceive the novel as its creator’s farewell to his Russian-language literary works and a milestone that denotes the beginning of Nabokov the American author.

The Gift might be most interesting for those already familiar with Nabokov’s poetry and prose. An average reader will also become fascinated with its style, its flight of imagination above the reality of our everyday life and its genre metamorphosis. Like any other Nabokov novel, it is a time-consuming journey, during which one makes discoveries that will remain with him or her for a while after the last page is turned.

Leave a Reply