The Museum of Modern Art might be the wrong place for “Joan Miró: Painting and Anti-Painting 1927-1937,†merely because most of their collection represents artists who dealt with either the joy or the agony of making art. It’s true that Miró revealed a great deal of agony through his work, but he discovered all kinds of joys in revealing it. During the years that inspired this collection, he tinkered with all kinds of paintings, models, collages and cartoons, all of them so complicated and strange that they risk losing their messages. That’s Miró for you: The agony of his art is that no piece was enough to contain his joy, and the joy is that those boundaries were ideal for interpreting his agony.

The Museum of Modern Art might be the wrong place for “Joan Miró: Painting and Anti-Painting 1927-1937,†merely because most of their collection represents artists who dealt with either the joy or the agony of making art. It’s true that Miró revealed a great deal of agony through his work, but he discovered all kinds of joys in revealing it. During the years that inspired this collection, he tinkered with all kinds of paintings, models, collages and cartoons, all of them so complicated and strange that they risk losing their messages. That’s Miró for you: The agony of his art is that no piece was enough to contain his joy, and the joy is that those boundaries were ideal for interpreting his agony.

Boundaries, by the way, are the key element in most of the work here. For Miró, it might’ve been a comfort to believe in control and limits while the real world moved closer to wartime anarchy. Even as early as 1928, he de-eroticized his fantasies through a series of collages known as the “Spanish Dancers,†where desires and fears were interpreted through physical facts like cork and sandpaper. With all the negative space “used†in the background, Paul Éluard’s famous comment that Miró had created “the barest picture imaginable†makes sense, but it’s the little things that hold the big questions: What makes a figure so reckless that it has to be nailed down?

It doesn’t matter. The point is that he’s holding himself back deliberately – the way every nail is carefully positioned along the figure’s margins calls attention to the hand that put them there. Maybe Miró did it that way to interpret some kind of mental struggle, working with precision to express imperfection.

That’s also true of the various models he put together in the early ‘30s, all of them proudly surreal and vulgar. The term “sculpture†doesn’t seem to apply here: Miró considered them merely as “Objects,†which used simplicity to challenge the mysteries of the real world. One’s got a piece of bone with an enormous nail going right through the middle of it, itself at a right angle with an old, thick plank. The plank stands along with other figures made of wood, their straight symmetry spelling out the fact that these were made by somebody. What makes it funny is that all of its dreamlike obscurity pretty much comes from squares and rectangles.

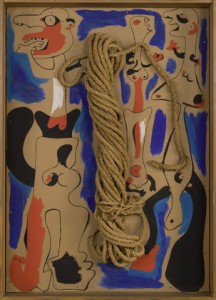

Perhaps Miró wanted to play with the laws of physics, as if viewing a rectangle as only a rectangle was precisely what made it more than a rectangle. Other objects required deeper thoughts, like the tangled cable at the center of “Rope and People I,†which physically hangs over primitive forms on the canvas. Most of his other works celebrate the use of tools in shaping the world, but this one feels like an omen – it probably won’t be long until somebody in the picture finds a way to turn it into a weapon.

Miró, on the other hand, was thoughtful enough to turn it into art, as if to give himself an example of humanity’s higher achievements.

Leave a Reply