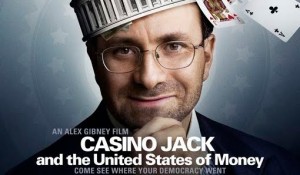

“Casino Jack and the United States of Money,†directed by Alex Gibney, is a documentary that’s at a right angle with its thesis: That its subject, Jack Abramoff (who starred in the film), was in total control of a shady controversy that ultimately bought him a 4-year prison sentence. In reality, so many people were involved with the whole thing that he was actually part of an even grander scheme – with politicians, Indian tribes and Christian activists working with him, you have to wonder why Abramoff had to deal with as much blame as he did. While that shouldn’t suggest that he didn’t get what he deserved (he is currently serving a prison term of nearly six years and will be released in December of this year), portraying him as the puppet master doesn’t seem right, with all the people he had onboard to help him out.

“Casino Jack and the United States of Money,†directed by Alex Gibney, is a documentary that’s at a right angle with its thesis: That its subject, Jack Abramoff (who starred in the film), was in total control of a shady controversy that ultimately bought him a 4-year prison sentence. In reality, so many people were involved with the whole thing that he was actually part of an even grander scheme – with politicians, Indian tribes and Christian activists working with him, you have to wonder why Abramoff had to deal with as much blame as he did. While that shouldn’t suggest that he didn’t get what he deserved (he is currently serving a prison term of nearly six years and will be released in December of this year), portraying him as the puppet master doesn’t seem right, with all the people he had onboard to help him out.

Abramoff pulled off one hell of a con job, but he didn’t do it alone.

Though the movie does call out pretty much every one of Abramoff’s cronies, there’s a sense that it doesn’t know how to handle them all. To be fair, it’s not easy to tell a story like this, particularly since Abramoff did so much lobbying on Capitol Hill that he wound up with clients who employed him for contradictory causes. He might’ve promised the American Indians he’d build support for casinos, but that didn’t stop him from taking money from Christian fundamentalists, who had some anti-gambling measures they wanted passed.

This is an even bigger rip-off than it looks like–Clint Eastwood pulled off the same con job in that old Western “A Fistful of Dollars.â€

Nor did Abramoff’s shady shenanigans end there. In what’s probably the most effective part of the film, we learn all about how he lobbied to make sweatshops in the Northern Mariana Islands possible, and the inhumane working conditions that the natives had to suffer through. With an hourly wage of little more than a dollar, many of the workers had to work 18-hour days while Abramoff’s cohorts vacationed on the beach.

As surprisingly underwhelming as this movie is, it’s difficult to deny how effective these scenes are, so much so that they might make Michael Moore envious. (They wouldn’t be out of place in Moore’s “Capitalism: A Love Story,†in fact.)

Part of the reason why that whole sequence works so well, though, is that it’s a rare moment where the film has some focus. For the most part, all this movie does is throw information up on the screen and hope that something will stick.

Even the humor that turns up now and then seems wasted – it’s really saying something when even footage of Tom DeLay going on “Dancing with the Stars†isn’t enough to make a film work.

This article originally appeared on AllMediaNY.com

I recently watched Casino Jack and the United State of Money, a new documentary about Jack Abramoff by filmmaker Alex Gibney, in a virtually empty movie theater. (Gibney won an Oscar for Documentary Feature in 2008.) Casino Jack regurgitated the identical story the media had proffered about “evil” Abramoff, and thematically repeated a documentary on Abramoff by Bill Moyers several years ago. Gibney’s film would have been a far more insightful and compelling work had it been even-handed.

Disclaimer: Even though I found his Abramoff documentary tendentious and flawed, I admire and respect Gibney and his work very much. Politically, we are both hard-core liberals. Because I was writing a book about Abramoff (and secretly interviewing him before and during his imprisonment,) Gibney and I have been occasionally meeting and talking about the Abramoff scandal for the past three years.

There are so many disappointing things with this documentary I don’t know where to begin. My overarching problem was that Gibney made no attempt to be objective, and that he omitted a plethora of important information that might have afforded the audience the opportunity to draw a more balanced, nuanced, and certainly more informed conclusion about this complex scandal.

Gibney apparently knew what his conclusion would be long in advance. Presumably for that reason, he did not interview anybody who defended Abramoff or anyone who argued that this scandal was far more convoluted than the simplistic, black-and-white narrative that has been repetitiously presented on the public and now by Gibney.

The film opens with footage of the 2001 mob murder of Florida businessman Gus Boulis, even though Abramoff had met Boulis only once and had absolutely nothing to do with his murder. (Boulis had just sold SunCruz casinos to Abramoff and his partner Adam Kidan.)

Soon, there is footage of the casinos operated by Abramoff’s tribal clients. Clearly, these casinos are on par with those in Las Vegas and Atlantic City. And clearly, these thriving casinos, earning hundreds of millions of dollars a year, belong to Indians who are well-to-do, not bumpkins that just fell off a log. They can afford the best consultants, lawyers, accountants, and lobbyists. Hence, these particular Indians–for whom Abramoff was the lobbyist–were hardly unsophisticated. Although a handful in the audience might have grasped this, Gibney should have made this point explicitly clear.

(A large part of what drove the virulent antipathy toward Abramoff was fueled by our collective guilt over the genocide that our European ancestors had committed against the Native Americans. In 1892, there were wild celebrations across the country. In New York City, for example, a statue was erected of the Great Navigator and the area was re-named Columbus Circle. But in 1992, there were essentially no national or regional celebrations to mark an extraordinary numerical anniversary: the quincentenary of the European discovery of the New World. The reason? We were too ashamed.)

Yes, the public was infuriated with Abramoff. Here was this white man–(the fact that he was an Orthodox Jew only made matters worse)–stealing candy from these poor and unsophisticated Indians. The Washington Post, which broke this story, exploited this undercurrent of shame brilliantly and cynically. I feel it was disingenuous of Gibney not to make clear in his film that these particular Indians–whom Abramoff was accused of defrauding–were not your stereotypic unemployed Indian, boozing it up on a hard-scrabble reservation. In the end, these Indians proved to be far more sophisticated than Washington uber-lobbyist Jack Abramoff.

The other impression that Gibney, The Washington Post, and Sen. John McCain, (former chair of the Senate Indian Affairs Committee, which also investigated Abramoff,) wanted to impart was that not only had Abramoff defrauded his clients, but he had been an ineffective and lousy lobbyist. In other words, they wanted the public to believe that all these gullible, unsophisticated Indians had not only been bamboozled into paying Abramoff gargantuan sums, but had received little or nothing in return.

This, however, is untrue. Abramoff was perhaps the most effective Indian lobbyist who ever lived. It would have been fair if Gibney had at least made that clear in his film. But he did not. Apparently, Gibney preferred Abramoff’s iconic image as the indelibly vile pariah, Indian exploiter, and corrupter of the democratic process.

TAXING TRIBAL CASINOS

The most compelling example of Abramoff’s lobbying magic was his successful efforts for three successive years to defeat Republican-controlled congressional legislation that would have taxed tribal casinos. (Federally recognized Indian tribes are “sovereign nations” and are supposedly exempt from federal and state taxes.) Had that legislation passed, tribal casinos would have been required to pay about 33% of their profits to the US Treasury. By killing this legislation, Abramoff has cumulatively saved Indian Country about $30 billion for the past 12 years and counting, exponentially far more than the relative pittance he charged them for his services. But once again, Gibney omitted this spectacular Abramoff triumph from his film.

THE CHOCTAWS OF MISSISSIPPI

Gibney describes how Abramoff, (remember, a lobbyist advocates for and protects his clients the same way a lawyer does), protected the interests of his client, the Choctaw Indians of Mississippi, so that its casino could keep making money. If a nearby casino were to open it would hurt his client’s revenue stream. So Abramoff worked hard to make sure no competing casino ever opened up. (This is precisely what anyone hiring a lawyer/lobbyist wants that person to do. This is the American Way, for better or worse.)

The Choctaws ran a very lucrative casino near the Alabama border. The Jena Tribe, also located nearby in Mississippi, wanted to open its own casino, which would have put a big dent in the Choctaws’ profits. But first, the Jena Tribe needed to get federal approval. With the help of Tom DeLay and other Republican lawmakers in Washington, Abramoff blocked the Jena’s casino. But Gibney made it seem that Abramoff’s successful efforts were somehow sleazy. Perhaps they were. But that’s not the point. Abramoff did his job. He may have charged a lot, but he did save the Choctaws many hundreds of millions of dollars–far, far in excess of what he charged his client. Gibney should have pointed that out.

Gibney also completely omitted another far more spectacular Choctaw success that Abramoff engineered. He somehow stopped a referendum in next-door Alabama that would have led to the opening of Indian casinos in that state. Since most of the Choctaw casino clients came from Alabama, the passage of that referendum would have probably put their casino out of business. Once again, Abramoff saved his client hundreds and hundreds of millions of dollars, something Gibney did not to mention.

THE COUSHATTA TRIBE OF LOUISIANA

Gibney omitted another impressive Abramoff lobbying coup involving the wealthy Coushatta Tribe of Louisiana, which also operated a casino and resort.

The Louisiana Coushatta had applied to the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) in 1927 for permission to purchase about 9,000 acres of land “in trust” to augment the size of its reservation. For nearly 75 years, the BIA did nothing but sit on that application. It was Abramoff, with the assistance of Tom DeLay, who forced the BIA to grant the Coushatta’s request. Again, Gibney made no mention of this.

Abramoff’s biggest lobbying coup for the Louisiana Coushatta was shutting down a casino east of Houston, Texas, that may have put his client’s casino out of business. It may seem hard to believe, but a complicating factor involved his also shutting down the casino of a tribe 1000 miles away in El Paso, Texas.

THE TIGUA TRIBE OF EL PASO, TEXAS

Gibney focused a lot of attention on the Tigua tribe of El Paso. This pivotal and controversial episode in the Abramoff scandal is the one which reporter Susan Schmidt of The Washington Post, (whom Gibney interviewed extensively in the film), manufactured so that Abramoff would appear to be the most deceitful villain who’d had ever slithered out of the slime.

Schmidt claimed that Abramoff had secretly shut down the Tigua’s casino simply so he could appear the very next day in order to persuade the tribe to hire him to get its casino reopened! The ultimate sleazebag, right? Well, not quite. It was Schmidt who was sleazy–some would say dishonest–in how she manipulated the facts. But her little work of fiction created such a firestorm of public fury against Abramoff that it helped her win a 2005 Pulitzer Prize, (which, in my opinion, should be rescinded.) What’s more, it was also the final straw that made Abramoff’s imprisonment inevitable.

The problem is that Schmidt withheld a crucial piece of information from her story. Here are the facts. (Please bear with me.This is a bit complicated.)

Back in 2001, there was one tribal casino in Texas, and it was being operated illegally (something Gibney neglected to mention) by the Tigua Tribe in El Paso. There was a second tribe preparing to open its own illegal casino 700 miles away, east of Houston. That second tribe is confusingly called the Alabama-Coushatta Tribe of Texas. A pending bill in the Texas state legislature would have legalized both tribal casinos. Abramoff’s client–the Louisiana Coushatta, (who had just purchased 9,000 acres of land thanks to Abramoff and DeLay), operated a very lucrative casino near the Texas border–felt very threatened. Most of its gamblers drove three hours from the Houston area to play slot machines and blackjack in its casino. Had the Alabama-Coushatta Tribe of Texas opened its own casino east of Houston, Abramoff’s client, the Louisiana Coushatta, might have been forced out of business. (Why drive three hours to gamble when a new casino has just opened minutes away?)

Here’s the point of this complex-sounding story. Abramoff needed to stop that Texas bill which would have legalized the two tribal casinos, even though only one of them–the Alabama-Coushatta Tribe of Texas–threatened his Louisiana client. Obviously, Abramoff had absolutely no interest in shutting down the Tigua casino, because it was located in El Paso, 1000 miles from (and therefore no threat to) his client in Louisiana. But, yes, if Abramoff could find a way to kill the bill, the Tigua casino would also be shut down.

In another brilliant lobbying coup, (which Gibney once again failed to point out), Abramoff managed to derail the Texas bill. (The bill had already passed in the Texas House by an 83-vote margin. It would have easily passed in the Texas Senate by an even greater margin, but Abramoff was somehow able to prevent the bill from ever reaching the Senate floor for a vote! Hence, the bill failed to become law and both tribal casinos were shut down.)

But The Washington Post’s Susan Schmidt never mentioned the part about the Alabama-Coushatta of Texas in her story! She claimed that Abramoff’s sole purpose was to shut down the Tigua’s casino so he could persuade them to hire him to get it reopened. She completely omitted the fact that the casino of another tribe–the Alabama-Coushatta Tribe of Texas–was the one and only one he was really interested in shuttering. Did Schmidt know that the Alabama-Coushatta Tribe of Texas even existed and that it was a threat to Abramoff’s client in Louisiana? Indeed, she did. Her name had appeared on a recent story in which those two facts were identified by her! Hence, it would appear that Schmidt deliberately omitted this key bit of information simply so her story would make Abramoff’s behavior seem so reprehensible.

I discussed this complicated story a number of times with Gibney. He didn’t seem as outraged as I. But he did end up conceding in his film that Abramoff’s shuttering of the Tigua casino was “collateral damage.” Schmidt, on the other hand, never used the term collateral damage–or any similar term, because that would have completely undermined her fairy tale of righteous indignation. She simply omitted the name of the second tribe and, most importantly, that the second tribe was Abramoff’s real target. Given Schmidt’s previous reporting, she knew that the real reason for Abramoff’s actions were not what she reported, but rather to protect his Louisiana-based casino client.

In the film, Gibney did not call Schmidt on the carpet for her gross journalistic transgression or question her on this matter at all. Why he gave her a free pass I find puzzling.

SEN. JOHN MCCAIN

Now, let’s take a look at the illustrious Sen. John McCain. Although Gibney was well aware that there was bad blood between McCain and Abramoff, he failed to mention this in his film. First of all, Abramoff was an arch conservative, allied with House Majority Leader Tom DeLay, anti-tax activist Grover Norquist, former Christian Coalition chairman Ralph Reed, right-wing ministers James Dobson, Pat Robertson, and others. They all loathed “maverick” John McCain, who at that time touted himself as a moderate Republican. Secondly, Abramoff had inadvertently funded the notorious and scurrilous “black baby smear” campaign that had helped to sink McCain’s presidential bid in the South Carolina Republican primary of February 2000. So it could be argued that McCain’s investigation of Abramoff was in large measure motivated by a personal vendetta. Gibney omitted this.

Although Gibney did mention that McCain had suppressed many of Abramoff’s subpoenaed emails, Gibney did not provide a readily available and widely known specific numerical percentage. The fact is that straight-talk McCain suppressed 99% of Abramoff’s emails! In other words, he only released 1% to the public. This highly selective release of emails allowed McCain to paint Abramoff in the worst possible light, especially since Abramoff foolishly decided not to defend himself during the hearings. (On advice of counsel, Abramoff exercised his Fifth Amendment right, which led many to conclude he was guilty.)

Gibney did point out that McCain suppressed many of Abramoff’s emails, but that he did so to avoid injuring his fellow Republicans. That was only partly true. The tiny fraction of emails McCain released had been selected and taken out of context in order to generate the greatest possible damage to Abramoff. Gibney knew this, because we discussed it many times, but did not mention it.

SUNCRUZ CASINO

Regarding the purchase of SunCruz casino, Abramoff had been indicted for wire fraud, involving a forged $23 million wire transfer. It was supposed to have been the down payment for the $147.5 million purchase of SunCruz casino. Abramoff, however, knew nothing about this phony wire transfer. I interviewed Adam Kidan, Abramoff’s SunCruz partner, for over 100 hours. I asked him if Abramoff had known about this forged wire transfer. Kidan repeatedly told me that Abramoff knew nothing about it. Since I had told Gibney this fact and since Gibney also interviewed Kidan for the film, I was quite surprised that Gibney did not mention it.

So why did Abramoff plead guilty to wire fraud in the SunCruz matter if he knew nothing about the concocted $23 million wire transfer? This is another key issue that Gibney chose not to address in his film.

WHITE-COLLAR GUILTY PLEAS AND HONEST-SERVICES FRAUD

Like many defendants, especially white-collar defendants, Abramoff decided to plead guilty, because he was afraid not to. (Indeed, the New York Times reported that over 25% of convicted and imprisoned rapists and murderers, later exonerated by DNA evidence, had pleaded guilty!) The truth is that Abramoff was intimidated and pressured into pleading guilty, even though he didn’t think he was guilty. First, his legal fees were becoming astronomical. Second, federal prosecutors were threatening to sentence him to 30 years in a maximum-security prison with violent offenders. Abramoff was told, however, that if he agreed to plead guilty to whatever they told him to plead guilty to, his sentence would be reduced to four years and he would do his time it in a cushy prison camp close to home, conveniently allowing his wife and five children to visit him. Once again, Gibney failed to mention this at all.

What exactly was Abramoff guilty of? Bribing congressmen? He never did that, (although he did plead guilty to it.) Tax evasion? Doubtful, (although he did plead guilty to this. Even some of the federal prosecutors who worked on the case strongly disagree on this tax-evasion charge.) Wire fraud? Definitely not, (though he did plead guilty to this too.) Defrauding his tribal clients? Well, now we’ve now arrived at the crux of the criminal matter, which centers on the “kickback” scheme involving Abramoff’s public-relations colleague, Michael Scanlon.

THE “KICKBACK” SCHEME

Gibney prominently mentions that Abramoff took “kickbacks” from Scanlon. The Post and McCain contend that Abramoff should have informed his tribal clients that he was getting a “kickback” from Scanlon, whom they hired at Abramoff’s behest. But there is nothing criminal in not informing his clients. And calling it a “kickback” is a misnomer. It was a perfectly legal referral fee, something that orthopedic surgeons, lawyers, and mortgage brokers engage in everyday without informing their clients. Federal prosecutors knew it wasn’t a crime, but they had to conjure up something to charge Abramoff with so he could appear to plead guilty to defrauding his tribal clients. The charge they conjured up was “honest-services fraud.” This is a nebulous felony that is impossible to define. In fact, a few days from now, the U. S. Supreme Court will probably declare this controversial law unconstitutionally vague…and yet Gibney chose not to mention anything at all about the storm swirling around the honest-services fraud statute.

THE GUILTY PLEA OF REP. ROBERT NEY

Gibney extensively interviewed former Ohio Congressman Robert Ney, who spent nearly a year in prison as a result of the Abramoff scandal. For a long time, Ney had stubbornly refused to plead guilty, claiming he had done nothing wrong. And in my opinion it is unlikely that Ney would have never been indicted, never mind found guilty of any charge related to the Abramoff scandal. What cooked Ney’s goose, however, was not Abramoff. Ney was caught accepting a $50,000 cash bribe from a Syrian businessman who asked Ney’s help in obtaining spare parts for Iranian military jets, something Abramoff had nothing to do with. With that little incriminating tidbit, however, federal prosecutors were able to tighten the screws on Ney until he squealed guilty to the Abramoff charges as well, in return for a reduced sentence in a cushy prison camp. Gibney knew all about that fat Syrian businessman, but did not to mention it in his film.

Gibney also mentioned that Ney had placed at Abramoff’s behest two statements in the Congressional Record–one that disparaged SunCruz owner Gus Boulis and a subsequent one that praised Adam Kidan. Well, this isn’t exactly true. Those statements had not been placed in the Congressional Record, but in the Congressional Records Extensions, an obscure publication that essentially no one reads, in which lawmakers insert statements praising local boy-scout troops; honoring a constituent’s birthday, marriage, or graduation; or expressing sadness over a constituent’s death. Gibney made a big deal out of that frivolous favor. Let’s face it. Frivolous comments made in an obscure publication pale in comparison to helping the terrorist state of Iran and sworn enemy of the United States obtain spare parts for its aging American fighter jets. But Gibney said nothing about this.

FORMER HOUSE SPEAKER TOM DELAY

As for Tom DeLay, former Republican House speaker and Abramoff’s most valuable asset, Gibney makes it clear how much he loathes his politics and his tactics–and so do I. And I can’t stand Abramoff’s politics as well, (even though he tried to change my mind during the 100 hours I interviewed Abramoff). Gibney did his best to make DeLay, who was extensively interviewed in the film, look hypocritical and sleazy. Gibney even included clips from DeLay’s embarrassing appearance on the TV show “Dancing With The Stars.” This was gratuitous and only served to make DeLay look foolish, which I thought was unfair. No matter how unsavory Gibney tried to make DeLay appear in the film, there is one incontrovertible fact Gibney had to concede: DeLay has never been indicted–(and never will be indicted, due to the statute of limitations)– for anything involving Abramoff. (And Abramoff, who has been cooperating with federal prosecutors for nearly five years, told me how badly they wanted to indict DeLay.)

ADAM KIDAN

Even minor things were not dealt with even-handedly in Casino Jack. For example, Gibney interviewed Melanie Sloan, executive director of CREW (Citizens For Responsibility and Ethics in Washington), a liberal, non-profit watchdog group. She stated that Adam Kidan, Abramoff’s SunCruz partner, had been disbarred for fraud. But Gibney chose not to give Kidan a chance to respond or defend himself. It just so happens that those charges were brought by Kidan’s stepfather, the controversial owner of adult video stores. They were embroiled in a business dispute. However, the stepfather later wrote to the authorities withdrawing his complaint. (These letters are archived and readily available in Brooklyn and Long Island courthouses.)

Furthermore, Naomi Seligman, former deputy director of CREW and one of Sloan’s dearest friends, used to date Kidan. Perhaps this was not worth mentioning in the film, but Gibney knew this.

THE EELEMOSYNARY ABRAMOFF

In the tradition of Orthodox Judaism, Abramoff had been an extraordinarily generous person. Essentially, he gave away much of his money, often anonymously, mostly to Jewish charities. He never even paid off his own home mortgage. And yet Gibney didn’t mention any of this at all. It’s as if he went out of his way to avoid saying anything that might cast Abramoff in a positive light.

CONCLUSION

Gibney ends the film decrying lobbying. He cites how banking and financial lobbyists are preventing the government from reigning in and controlling derivatives, such as credit-default swaps, which recently nearly triggered an economic depression. He also cites the recent Supreme Court decision, allowing corporations to spend as much as they want on lobbying. And somehow he compares those cataclysms to the alleged crimes of Jack Abramoff.

What crimes did Abramoff actually commit? He got Rep. Bob Ney to insert frivolous comments in the frivolous Congressional Records Extensions. Abramoff gave lawmakers and their staff free meals, drinks at his restaurant and free seats at sporting events, and subsidized a few golf trips. And what did he get in return? He helped his tribal clients’ casinos remain profitable. He wangled an audience with President George W. Bush for the prime minister of Malaysia. So what? This is inconsequential compared to the great evils perpetuated by the financial-industry lobbyists, the health-care lobbyists, the tobacco lobbyists, the National Rifle Association, etc. And for these petty gems of sleaze and corruption, Abramoff is sent to federal prison for four years? Seems to me like much ado about nothing.

What Gibney did not mention in his film is that lobbying–the right to petition Congress–is protected by the very First Amendment to the Constitution. Sure, every liberal wants elections to be publicly financed, but it will never happen because of something called the “incumbency advantage.” Incumbents get reelected about 90% of the time, thanks, in part, to the money that lobbyists funnel into their reelection campaigns. (Yes, the “bad” lobbyists include Exxon Mobil, the National Right to Life Committee, and the National Rifle Association, as well as the “good” lobbyists like the American Civil Liberties Union, the NAACP and the AARP.) It’s doubtful that current lawmakers are going to pass legislation that would make it easier for their opponents to take away their jobs.

When Abramoff stopped the Republican-controlled Congress from taxing Indian casinos, do you know how he did it? He didn’t do it with free drinks and meals at his restaurant, free tickets to sporting events at his skyboxes, or golf trips. What those freebies got him was access to the lawmakers and their staff, so he could present a compelling argument. And what was that compelling argument that killed the bill? He told Republican lawmakers that they should vote against this bill because it was a tax, and Republicans were supposed to be anti-tax fanatics. It worked, but people who see the documentary won’t know that, because Gibney didn’t mention it.

Oh yes, I almost forgot. Remember those naïve, unsophisticated Indians that Abramoff bamboozled? Well, they all sued the law firms that Abramoff used to work for. And guess what? They all won huge settlements, so that in the end, they got Abramoff’s phenomenal lobbying services for a pittance…Gibney forgot to mention that too.

Gary S. Chafetz is the author of The Perfect Villain: John McCain and the Demonization of Lobbyist Jack Abramoff.